Gio Ponti was the third architect contacted about designing the Denver Art Museum, and due to his interest in building something in the American West, and personal relationship with Sudler, Ponti accepted the job and spent the last decade of his life working on this project.

The DAM’s many locations

Not only is the Martin Building Ponti’s only completed building in North America, but it also served as the first landmark building for the DAM. Originally founded in 1893 as The Artists’ Club, the institution spent decades moving from one temporary location to another, before finding a permanent home in 1922 at the Chappell House at 1300 Logan Street. For the next three decades, the museum became known for the energetic and imaginative programming for diverse audiences.

Capitalizing on the postwar growth in the region and rising levels of cultural ambition throughout the country, then-director Otto Karl Bach was instrumental in planning and executing the vision of a landmark building that would house an encyclopedic collection under one roof, making art of all periods accessible to the people of Denver and the Rocky Mountain Region.

The pursuit of light and the exterior façade

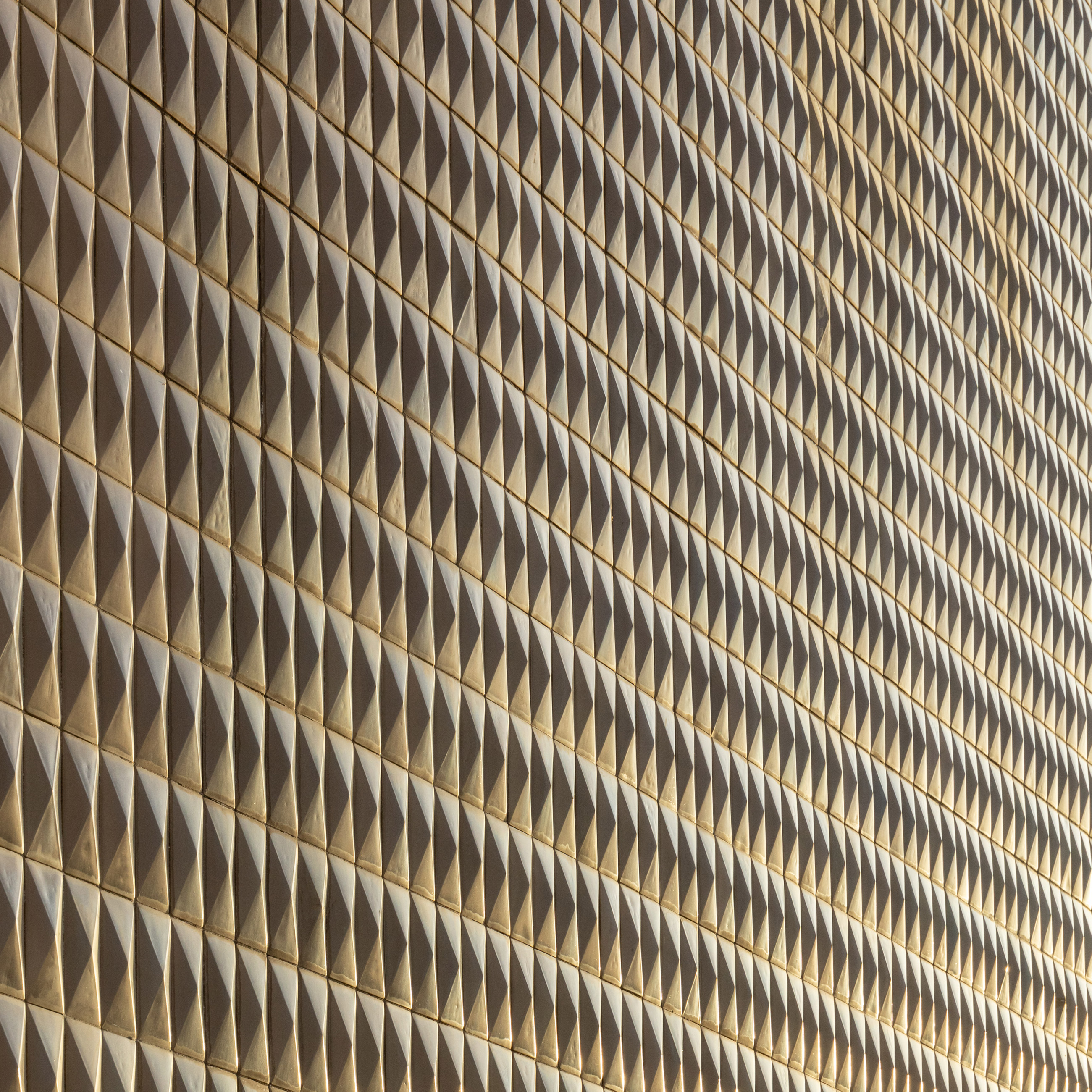

Ponti originally intended to use ceramic tiles for the exterior of the building, as he wanted to create the illusion of an exceptionally light and delicate structure. However, Ponti and Sudler decided that ceramic would not sufficiently hold up to the demands of Colorado's extreme weather and decided to use tiles made of warm gray glass instead. The glass tiles fulfilled Ponti’s vision of using the surface of the building to channel the bright Colorado sunshine, creating a shimmering effect across the exterior of the building.

Designed by Ponti and originally produced by Dow Corning, approximately one million tiles were hand set over the course of two years before being installed on the exterior of the building. To replace the tiles that had fallen off the building over the years, the DAM received special permission from Corning to use the file patented design to produce 17,000 new tiles by German company Bendheim.

1992.514: Portrait of an Architect Tile, about 1930. Ceramic (earthenware). Manufactured by Richard-Ginori, Milan. Denver Art Museum: Gift of Art After Hours, 1992.514.

The many talents of Gio Ponti

Although Gio Ponti was trained as an architect, he started his career as a designer of ceramics as the art director at Richard Ginori, the historical Italian porcelain manufacturer. Tile was often Ponti’s material of choice for a building’s flooring, interior, and even exterior. Over the course of nearly five decades, Ponti became an internationally celebrated architect, an industrial and decorative designer, a costume and set designer, a professor, and the editor of two influential magazines, Domus and Stile.

In addition to the completion of many buildings around the world from his native Italy to Venezuela, Ponti was also a tireless designer who created imaginative and innovative designs, from designs like the spoon, to ceramic tiles, and even furniture. You can see more of Ponti’s design work in the exhibition Gio Ponti: Designer of a Thousand Talents, opening on October 24.

A focus on the entire design

Ponti’s diverse achievements and influence as one of the leading figures among modern Italian architects and designers was influential in defining and shaping Italian and European culture. Ponti’s design—Classic, Modernist, and Brutalist—was avant-garde and structurally innovative in its day.

Ponti’s attention to the exterior of the building, in conjunction with Sudler and Bach’s focus on the interior spaces of the museum and making it as visitor-friendly as possible, set a precedent for the museum’s confidence that the container is as equally important as what is contained, and a focus on shaping the entire design of the museum building.

This philosophy is articulated in this quote by Gio Ponti:

The most resistant element is not wood, is not stone, is not steel, is not glass. The most resistant element in building is art. Let’s make something very beautiful.