Students will look at and discuss Coen’s painting Yellow Rain Jacket and write stories from the perspective of either the horse or the champion rider, exploring how the same details can be communicated differently.

Students will be able to:

- identify and describe visual and storytelling details in a painting;

- acknowledge how an artist can find inspiration in everyday happenings;

- draw conclusions about the relationship between the horse and rider; and

- write a story from another’s perspective.

Lesson

- Warm-up: To stimulate abstract thinking, sit the class in a circle and, going around the circle, have each student name one thing that is red. Go around the circle as many times as you can until the students run out of ideas. If a student gets stumped, they are eliminated until the next round. Repeat, this time asking for things that can make a person happy or upset, things that can be made from a potato, etc.

- Show students Donald Coen’s painting Yellow Rain Jacket and ask them to discuss what the subject of the painting is. Some students might think the horse is the subject, some the saddle, and some the yellow rain jacket. Have the students list as many details as possible (saddle, stirrups, jacket, saddle horn, rope, mane, leather engraving, horse’s veins). What’s their favorite part of the painting?

- Using the About the Art section, explain that this painting was inspired by a trip to Cheyenne Frontier Days, a yearly celebration of the West in Wyoming. What types of events might happen at a celebration of the West (rodeos, parades, country music concerts)? What would they smell at Cheyenne Frontier Days (food, animals)? What sounds would they hear?

- Discuss the relationship between the horse and its rider. Prompt the students with questions such as: How can you tell this horse isn’t wild? How can you tell he has a rider? Do you think the horse is tired of carrying the saddle and rider, or is he excited about the rodeo? What could the rider be doing while the horse is standing here?

- Divide the class in half and explain that one half of the class will write a story about the celebration from the horse’s perspective. The other half will write a story from Champion Team Roper’s perspective. You could also allow the students to choose which perspective they want to write from. Encourage students to incorporate smells, sounds, sights, etc. With younger students, write a story as a class and record it on the board.

- When the students have finished, have them share their stories with each other in small groups.

Materials

- Pencils/pens and paper

- About the Art section on Yellow Rain Jacket

- One color copy of the painting for every four children, or the ability to project the image onto a wall or screen

Standards

- Visual Arts

- Observe and Learn to Comprehend

- Relate and Connect to Transfer

- Language Arts

- Oral Expression and Listening

- Research and Reasoning

- Writing and Composition

- Reading for All Purposes

- Collaboration

- Critical Thinking & Reasoning

- Information Literacy

- Invention

- Self-Direction

Yellow Rain Jacket

Donald W. Coen, United States

1989

54 in. x 73 in.

Denver Art Museum Collection: Gift of the artist, 2000.84

Photograph © Denver Art Museum 2009. All Rights Reserved.

Don Coen was raised on a ranch in Lamar, Colorado, and now lives in Boulder. As a kid, he made hundreds of cowboy and Indian drawings, inspired by the likes of Frederic Remington and Charles Russell. He also sketched maps, people, and comic book characters while listening to the radio at night. “Thank God we didn’t have TV,” he says. Coen went on to study art at the University of Denver and the University of Northern Colorado. At that time art was all about abstraction, so most of his early paintings focused less on realism and more on color and form. Several years later, on a trip back to the Lamar family ranch, Coen witnessed a stunning plains sunset that led him to return to subjects of rural western life. He says:

I feel what I am doing is important because this type of life—farm and ranch life—is changing rapidly. It seems like every day a farm family goes out of business. These are proud, honest, hard-working families whose story has never been told in art. I’m trying to tell that story in my work. I feel I have a kinship with them in that I spent the first 20 years of my life on a farm.

Coen’s signature tool is the airbrush, which he likes because he can achieve a highly luminous paint surface. His airbrush applies paint in extremely thin coats, and Coen creates rich, sophisticated colors by strategically layering them. “The color you put underneath has a tremendous effect on the color on top. It always shows through. If you want to paint, say, a brown area, you shouldn’t ever use brown paint but colors that, mixed together, will give you brown.” He doesn’t use white paint, but simply allows more or less of the white of the canvas to show through. Some areas of his paintings have as many as 70 light coats of paint, and each painting takes three or four months to complete.

In place of his childhood visions of romantic cowboy adventures, Coen chooses to focus on quiet, ordinary moments in today’s rural West. As a contemporary ranch insider, he strives “to show the truth and the beauty and simplicity of what’s really happening in rural America, without all the clichés that go with it.”

This painting was inspired by a trip to Cheyenne Frontier Days, a yearly celebration of the West in Wyoming. Coen likes to arrive at the fairgrounds very early, before any other visitors are there, and watch the cowboys milling about with their horses tied up, getting ready for the day. He says, “I just loved how this yellow rain jacket was on the back of this saddle, the look of the saddle, the way the light was hitting on it, the way the horse was standing there; it was a great image.”

Details

Focus

Coen carries a camera everywhere, shooting hundreds of images, and he creates paintings from his own photographs. He shoots his source photos with a telephoto lens, which for this piece allowed greater focus on the objects in the foreground while blurring those in the background. He creates a telephoto effect in the painting with softer focus on objects farther away.

Hints of a Story

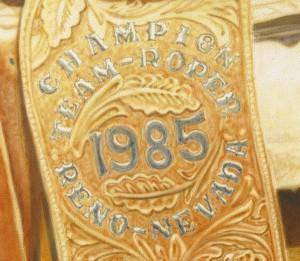

The text on the saddle, “Champion Team-Roper, Reno-Nevada, 1985,” is located smack in the middle of the painting and it introduces a person you don’t see—the champion team-roper. The story of the rider isn’t in the action you see or in expressions you can interpret, but we can look for clues given by the artist:

• the yellow rain jacket, and its significance implied by the title;

• the rope hanging over the saddle horn;

• the back end of another horse nearby; and

• visible wear from the buckle on the saddle strap.

Black Mane

Coen does not use black paint, yet there are parts of this painting that look black. If you look closely at the hairs of the horse’s mane, for example, you can see that they are actually composites of color, built up with layers of blue and purple.

Contemporary Details

The black material wrapped around the saddle horn, or handgrip, is made of inner tube strips—modern day team ropers do this so that a rope will catch and not slide off the saddle. Coen thinks too many Western artists are frozen in the past; he likes to show the West as it really is.

Soft Lines

Coen painted Yellow Rain Jacket with an airbrush. Airbrush guns break down paint into very fine particles and use compressed air to spray the paint onto the canvas. Coen prefers to create a “soft edge, a personal kind of edge” with his airbrush. When he needs to paint an edge, he designs a plastic stencil and attaches it to the painting with rolled-up pieces of masking tape, rather than putting the stencil flat against the canvas. This way the paint bleeds over the edge, creating a blurry line.

Dot Patterns

One of the reasons Coen likes using an airbrush is for the dot pattern it can create. Areas with a dot pattern are blurry up close, but they resolve into objects when you move away from the painting—like the effect Coen got as a kid when he would stand close to a large movie screen. He creates different sizes of dot patterns with different airbrushes.

Cropped View

In this painting, Coen focuses on the central part of the horse, with the head, mane, tail, and legs cropped away. By photographing just this part of the horse, he is able to notice things he initially missed, like the veins on the horse’s neck or the little piece of the mane that is slightly raised as if in a breeze.

Large Canvas

Yellow Rain Jacket is nearly 4 ½ feet tall and 6 feet wide. Coen likes really large canvases, partly because of his experience with big views on the plains and also because of his fondness for film and old, big-screen movie theaters. He also likes how you can be absorbed into a large painting. Working with an airbrush, Coen needs to maintain a careful position in relation to canvas, so he has rigged up a pulley system in his studio that allows him to raise or lower his large canvases through a slot he’s cut out in the floor. Supporting his wrist to keep steady, he slowly and carefully sprays as he walks back and forth.

Funding for object education resources provided by a grant from the Morgridge Family Foundation. Additional funding provided by the William Randolph Hearst Endowment for Education Programs, and Xcel Energy Foundation. We thank our colleagues at the University of Denver Morgridge College of Education.

The images on this page are intended for classroom use only and may not be reproduced for other reasons without the permission of the Denver Art Museum. This object may not currently be on display at the museum.