Isamu Noguchi y Isamu Kenmochi, “Basket Chair” (Silla de cesto), 1950, creada en 2008. Bambú, madera y hierro; 28 ⅞ x 34 1/2 x 30 pulg. Lutz Bamboo Collection en el Denver Art Museum: Donación de Adelle Lutz en honor de Ronald Otsuka, 2010.406.

Inspired By:

Basket Chair by Isamu Noguchi and Isamu Kenmochi

Topic:

Learn how design uniquely combines aesthetics and function through the design process.

Rationale:

By considering how design connects with their daily lives, kids will discover how designers think and create, empowering them to shape and design the world around them.

Resources Include:

For Facilitators:

- This how-to facilitation guide (includes information on theme and individual artworks, links for background research, a video highlighting the artwork, and a video demonstrating the art project)

- Links to high resolution images of the artwork

- Teaching slides with condensed information and discussion questions: Elementary and Middle/High School

For Kids:

- Instruction sheet for the artmaking project

- Virtual Spinner

- What is Design?

- What makes design unique?

- Learn more about this object

- Weaving Innovations

- Activity Extension

- Define the problem

- Iteration

- Your Turn

What is Design?

Design is the method of putting form and content together. Design, just as art, has multiple definitions; there is no single definition. Design can be art. Design can be aesthetics. Design is so simple, that’s why it is so complicated.

Design is all around us, whether it takes the form of objects and spaces, images and interactions, or systems and processes. Design shapes our lives in fundamental ways, and we, as designers ourselves, can shape design by participating in the creation of it. Beyond meeting a need, design can be an expression of a concept or aesthetics (beauty) and can experiment with forms, techniques, or materials.

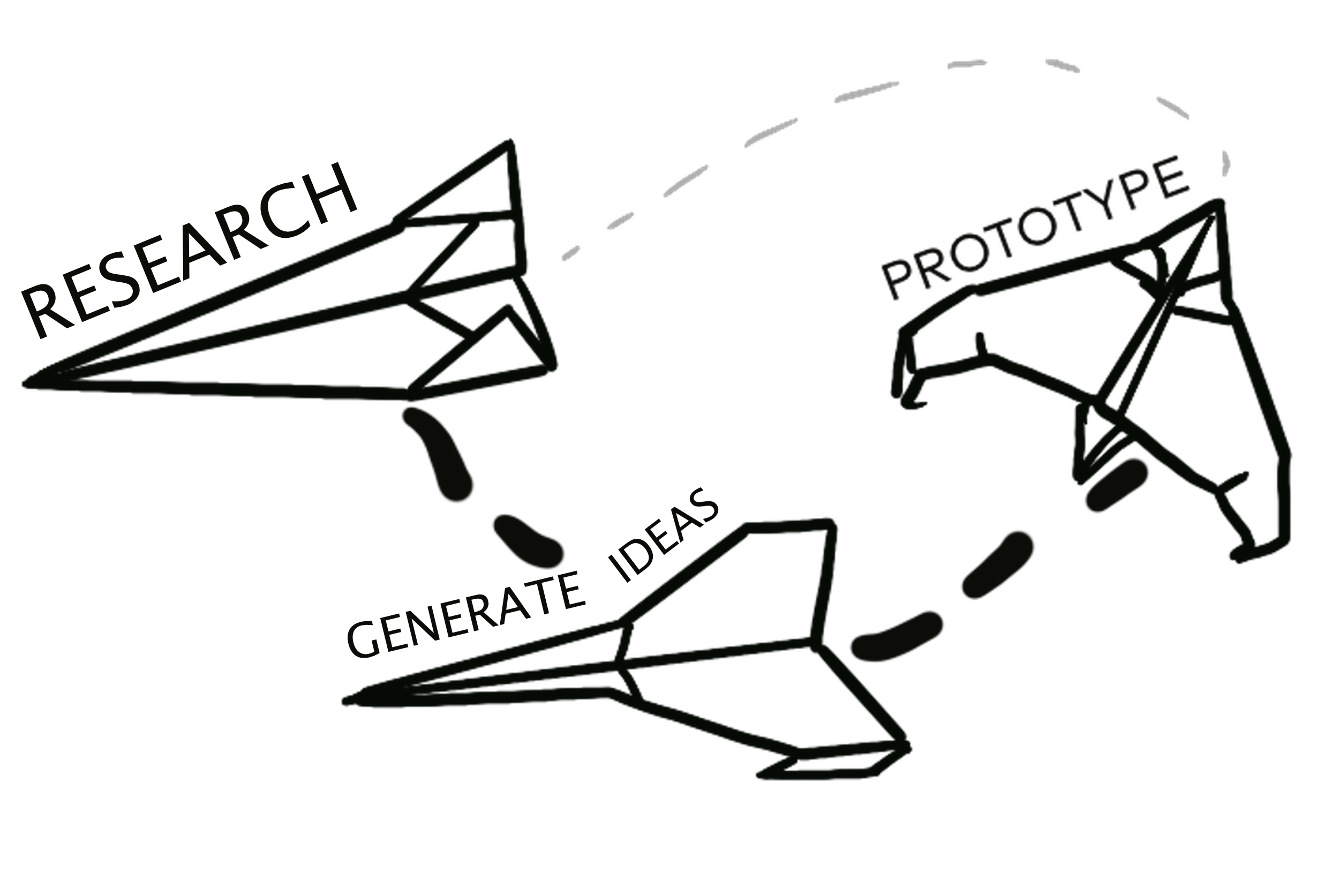

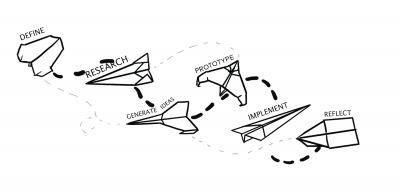

Design involves a creative problem-solving process. Design is not fully linear or sequential; it is not simply a straight path from point A to point B. The process often has many cycles and jumps back and forth among stages of the process until a solution has been found. Each project invariably has its own unique path. No matter what kind of design problem you are trying to solve, you will most likely engage with these key phases:

- Define: Start with a question or need.

- Research: Learn about your problem and users.

- Generate ideas: Brainstorm and come up with as many solutions as you can.

- Prototype: Test your ideas using models and sketches.

- Implement: Produce your best idea.

- Reflect: Evaluate, seek, and incorporate feedback.

What makes design unique?

Design sits at the intersection of empathy and creativity. While some might argue that art and design are not synonymous, others feel design is where aesthetics and utility become blurred. Beauty might be subjective and in the eye of the beholder, in which case it is not simply superficial. It is difficult to separate the content of a work and its form; thus designers have a unique ability to instill beauty into their work in order to stimulate our senses and connect an item to the culture in which it is produced. Great designers find solutions and the aesthetics that accentuate its value.

Watch Denver Art Museum Through a Different Lens: Weaver and Engineer Discuss Basket Chair featuring the Basket Chair by Isamu Noguchi and Isamu Kenmochi and consider the form and function of this design.

Conversation Questions

- Why are chairs the way they are, or what elements make a chair? What do you think impacts how they are designed?

- What makes the Basket Chair unique?

- What connects the Basket Chair to Japanese culture?

- What materials is this chair made of? Why might the designers have chosen these materials?

- What kind of problem does weaving the bamboo in this chair solve? Or how does weaving the bamboo in this chair solve a problem or need?

- What influenced the form (shape) of this chair?

Learn more about this object

Isamu Noguchi y Isamu Kenmochi, “Basket Chair” (Silla de cesto), 1950, creada en 2008. Bambú, madera y hierro; 28 ⅞ x 34 1/2 x 30 pulg. Lutz Bamboo Collection en el Denver Art Museum: Donación de Adelle Lutz en honor de Ronald Otsuka, 2010.406.

This collaboration between Isamu Noguchi (a Japanese-American sculptor) and Isamu Kenmochi (a Japanese industrial designer) expanded the concepts of both Western and Japanese modernism. This chair exemplifies their aspirations to create universally functional objects that also incorporate the basic beauty of simplicity grounded in a knowledge of natural materials. They also embraced experimental techniques and resources.

The bamboo Basket Chair was designed as a prototype for mass production, although ultimately it was not produced for the general public. While Noguchi was not specifically looking to incorporate Western design with a Japanese aesthetic, Kenmochi was deeply interested in remaking the chair for daily use in Japan.

Tatami mats are a traditional type of seating in Japan and are part of important cultural traditions such as meditation and the tea ceremony. In the 1920s the use of chairs more commonly in Japan began, in both public and private places, due to the globalization of business. For both designers, the process of creating the experimental bamboo chair (in 1952) was dedicated to the purpose of advancing the modernization of Japanese forms in tandem with the use of traditional Japanese techniques and materials that could be brought together for a Japanese and foreign market.

Dig Deeper (helpful links)

Weaving Innovations

Isamu Noguchi y Isamu Kenmochi, “Basket Chair” (Silla de cesto), 1950, creada en 2008. Bambú, madera y hierro; 28 ⅞ x 34 1/2 x 30 pulg. Lutz Bamboo Collection en el Denver Art Museum: Donación de Adelle Lutz en honor de Ronald Otsuka, 2010.406.

An interesting quality of the Basket Chair is that it is woven with bamboo strips. Weaving is a centuries-old art form with a rich and extensive history that continues to evolve. From a necessary household chore to a skill-driven occupation to a form of personal expression, weaving has been re-envisioned and transformed by generations of dedicated makers. Weaving is a practice that transcends cultural boundaries. Examples of different techniques and uses from cultures around the globe emphasize how the craft reflects cultural traditions. Today, contemporary artists, designers, and craftspeople are producing exciting new work drawn from the lessons of those who came before. The materials used and their varied applications make for incredibly surprising objects in an array of forms. Compare this bamboo Basket Chair to these other woven artworks (historic and contemporary) in the Denver Art Museum collection.

Consider the cultural influences of weaving and bamboo on the Basket Chair

Conversation Questions

- What materials can you spot?

- How did each of these artists apply weaving techniques differently?

- What is surprising about these weavings to you?

Dig Deeper (helpful links)

Activity Extension

Basket Chair is just one chair in a long history of chairs, and of designers exploring the design process, making it a perfect place to start. Learn about design thinking by looking at two aspects of the process–define and iterate–using the evolution of the office chair as an example.

Throughout history, chairs have encapsulated the life and times of designers and consumers. Like any work of art, a chair’s construction, materials, maker, and style can tell volumes about the culture from which it emerged. Materials and methods of production multiplied by imagination yields a nearly unlimited number of solutions to the problem of where to sit. What was important at the time?

Who were they made for? What spaces did they inhabit? As art and design evolve over time, chair design does too. However, the primary purpose has not changed–for millennia, people have needed a place to sit. As such, the chair is a perfect marker for the ever-changing history of design. Check out just a few of the chairs in the Denver Art Museum collection and use these discussion questions to frame your understanding of the design process.

Define the problem

Iteration

As a group, rearrange these task chairs found on pages 8 and 9 chronologically, based on the dates found on the labels.

Conversation Questions

- What are some of the changes you notice in chair design over time?

- Why do you think that is?

- Which elements of these chairs have remained the same?

- Why do you think that is?

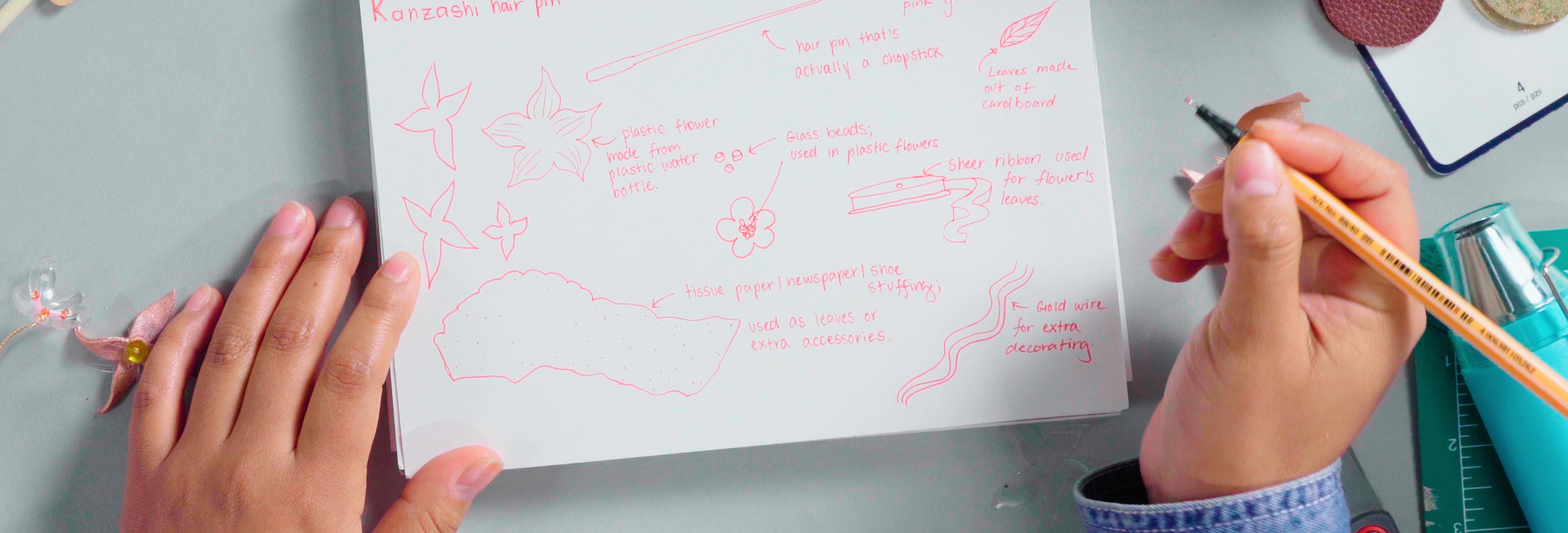

Your Turn

After learning how designers blur the boundaries between beauty and utility, are inspired by culture, and experiment with form and materials with chairs, it is your turn to think like a designer and redesign the world around you. We will intentionally start designing with our own ideas of beauty, in order to investigate the role of aesthetics in the design process.

- Make a list of interesting objects that are useful/purposeful in your life. (e.g., headphones, a teapot, sneakers, etc.)

- Choose one object to redesign with your own requirements for beauty/intrigue in mind. Consider how cultural elements that are important to you could play a role in how your object looks. Think about how your material choices impact your design, just like the use of bamboo in the Basket Chair.

- Prototype your idea: create a drawing or 3D model (life-size or miniature).

- Share your redesign with others and collect their feedback. How do they feel about how it looks? How do they feel about how it works?

- Next you are redesigning for another user. Use this Virtual Spinner to select an end user for your object. Miles the Bronco, Harry Potter, Black Panther, Sponge Bob, Among Us Crewmate, Ms. Marvel, Nya-Nya/Miko Tezumi (Teen Titans), Hector Rivera, Hello Kitty.

- Empathize with your end user. What do you think their needs might be? And why? Look up any information about your end user that you can.

- Iterate your design by making another version of your drawing or prototype.

- Share your newest iteration with others and collect their feedback.

- Continue reflecting and iterating as many times as you would like.

Reflection Questions

- What was it like for you to make multiple iterations of your design and receive feedback?

- How did feedback affect the end result?

- In what ways did you combine utility and aesthetics in any of your iterations?

- How was your design affected by culture?

- In this challenge you designed for beauty and intrigue first. What effect did that have on your work? Were there any drawbacks to this approach?

- What might have happened if you had designed with another person’s needs in mind before you considered beauty and intrigue?

- What other objects might you want to redesign in your world?

Chairs for Iteration Activity

Como grupo, ordenen cronológicamente estas sillas de trabajo, basándose en las fechas que se encuentran en las etiquetas.

Centripetal Spring Side Chair

Thomas E. Warren, Centripetal Spring Side Chair, about 1849. Painted cast iron, painted steel, wood, and original upholstery; 21 ½ × 18 ⅞ × 20 ½ in. Manufactured by American Chair Company, Troy, New York. Denver Art Museum: Funds from DAM Yankees, 1989.91.

Thomas E. Warren, American Chair Company, 1849

The American Chair Company was primarily a maker of railway-car seating that had spring-based devices designed to absorb shocks during high-speed movement. Thomas E. Warren’s centripetal spring chair was one of the company’s earliest household products. Praised for its innovative spring mechanism at the 1851 Crystal Palace Exhibition in London, Warren’s design swiveled and turned in the manner of a modern desk chair.

Aeron Chair

Donald Chadwick and William Stumpf, Aeron Chair, 1994. Glass-reinforced polyester, die-cast aluminum, and Pellicle synthetic and leather upholstery; 39 1/4 x 25 x 25 in. Manufactured by Herman Miller, Zeeland, Michigan. Denver Art Museum: Gift of the manufacturer, 1995.252. Image courtesy Herman Miller.

Donald Chadwick, William Stumpf, Herman Miller, Inc. 1994

The Aeron debuted in 1994. It was designed to provide ergonomic support and to innovate materials by using mesh instead of foam, fabric, or leather. After its debut, the chair became a status symbol in Silicon Valley, an area known for a high density of technology companies.

Perch Chair

Robert Propst, Perch Chair, 1964. Chrome-plated steel, leather, latex foam, and cast aluminum; 40 1⁄4 × 21 3⁄4 × 28 1⁄4 in. Manufactured by Herman Miller, Zeeland, Michigan. Denver Art Museum: Gift of Elizabeth Torke Jones in memory of David R. Torke, 2012.320.

Robert Propst, Herman Miller, Inc. 1964

Robert Propst designed the Perch chair as a resting place for people who primarily work standing up. It was part of Action Office I (AO-1), a modular office furniture system manufactured by Herman Miller. Propst’s research into working environments led him to realize the benefits of standing while working well before the term ergonomics was widely understood.

Sayl Chair

Yves Béhar, Sayl Chair, 2011. Steel, plastic, aluminum, polyurethane foam, and recycled polyester upholstery; 33 3⁄4 x 24 1/2 x 16 in.. Manufactured by Herman Miller, Zeeland, Michigan. Denver Art Museum: Gift of Workplace Resource of Colorado and Herman Miller, 2019.642.

Yves Béhar, Herman Miller, Inc. 2011

The Sayl chair has a Y-shaped support which creates an interesting visual look and is inspired by suspension bridges. The chair structure deliver the most ergonomic support while using the least material, making it eco-friendly.

Synthesis 45 Typing Chair

Ettore Sottsass, Synthesis 45 Typing Chair, 1971. Injection-molded ABS plastic, polyurethane foam, and upholstery; 34 1/2 x 21 1/2 x 23 in. Manufactured by Ing. C. Olivetti & C., Ivrea, Italy. Denver Art Museum: Gift of Dr. Robert Blaich, FIDSA/FRSA, 1999.183. Image courtesy VINTAGE.

Ettore Sottsass, Albert Leclerc, Masanori Umeda, Olivetti 1971

Ettore Sottsass began designing individual office equipment before becoming interested in creating ideal, holistic workspaces. The Synthesis 45, a typing chair, is part of a whole suite of furniture. Sottsass became known for his vision to move away from functionalism and focus more on emotion, feeling, and beauty in his work.

El DAM estableció los Recursos creativos gracias a una generosa donación de la fundación Morgridge Family Foundation. Las actividades presentadas han contado con la financiación de los fondos de la fundación Tuchman Family Foundation, la Freeman Foundation, la Virginia W. Hill Foundation, la Sidney E. Frank Foundation, el fondo Colorado Fund, Colorado Creative Industries, la fundación Margulf Foundation, la Riverfront Park Community Foundation, Lorraine y Harley Higbie, un donante anónimo, y los residentes que dan su apoyo al Distrito de Organizaciones Científicas y Culturales (SCFD por sus siglas en inglés). Un agradecimiento especial a nuestros colegas del Morgridge College of Education de la Universidad de Denver. El programa Free for Kids en el Denver Art Museum es posible gracias a Scott Reiman, con el apoyo de Bellco Credit Union.