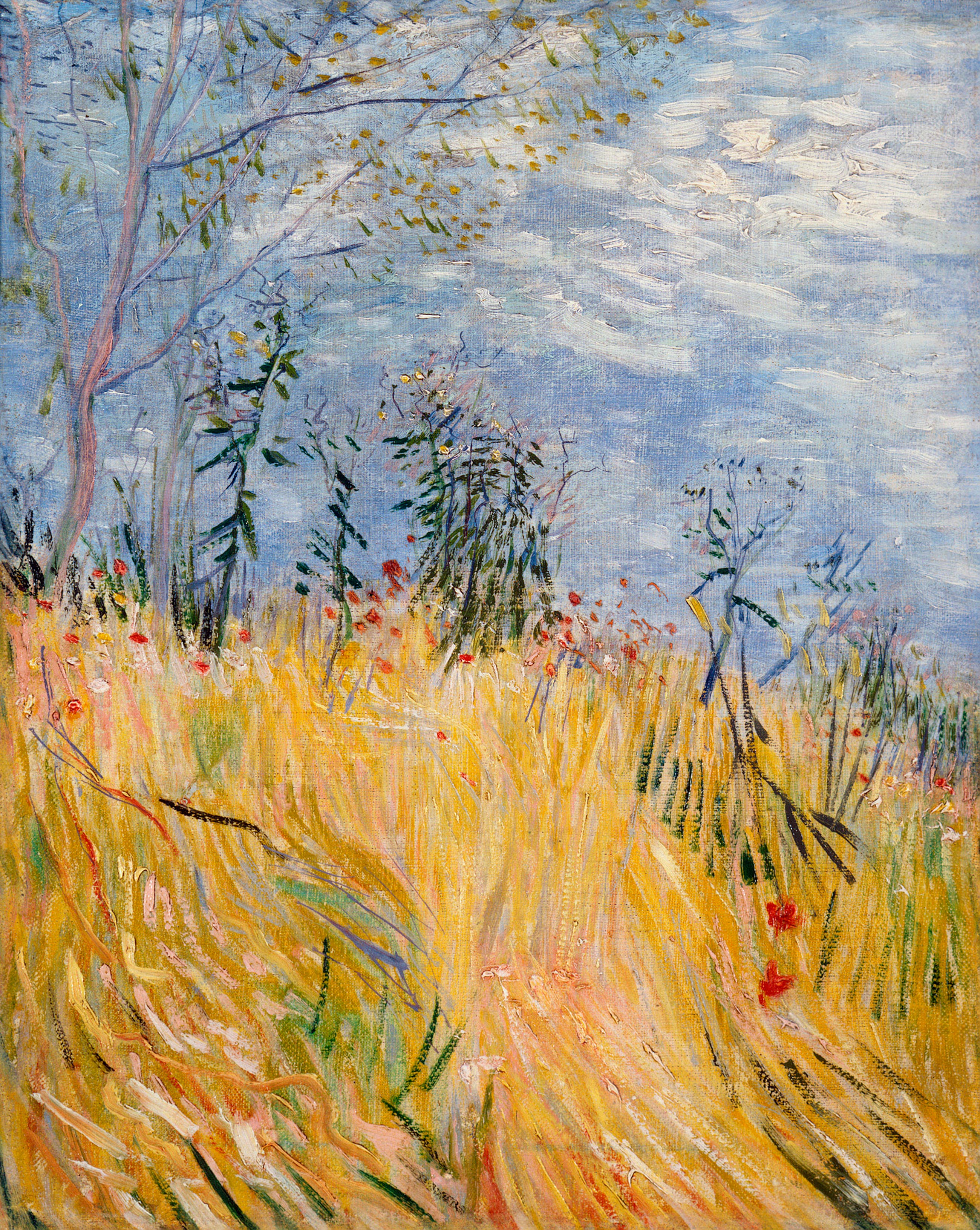

Vincent van Gogh, Borde de un campo de trigo con amapolas, 1887. Óleo sobre lienzo sobre cartón. Colección Frederic C. Hamilton, legado al Denver Art Museum. 35.2017.

Edge of a Wheat Field with Poppies, made in the summer of 1887, gives a sense of the many influences van Gogh was exposed to during his first year in the “hotbed of ideas” [as he called Paris in a letter to his sister].

The small painting captivates us with its bright contrast between the orange yellow of the field and the complementary radiant blue of the sky, the dark green of the new shoots coming up and the vivid vermillion of the poppies, sprinkled across the canvas in free dashes. The vertical space is evenly divided between earth and sky. The vantage point is surprisingly low to the ground; we look at the scene as though up a hill. This is not the vast expanse of field shown in Caillebotte’s painting or van Gogh’s later landscapes, but a detail—a highly fragmented view. A slender poplar arcs along the left edge of the painting, and clusters of budding stalks seem to dance on the horizon line.

With no identifying urban features inside the frame, it is impossible to say whether van Gogh’s wheat field was located in Montmartre, where he was living at the time, or in the vicinity of Paris. While the city of one million inhabitants lay spread out at his feet on one side of the hill of Montmartre, the original rural aspect of the neighborhood was still visible on the other, close by his apartment. Montmartre had been incorporated into the city only a few years earlier, and the far side of the hill was still largely rural in character, complete with vegetable gardens, fields, and windmills, as well as a wide view over the open expanse of the Île de France. This area and the nearby village of Asnières, where he painted views of the Seine and of leisure life, provided van Gogh with many of his rural motifs during his two-year stay in Paris.

The upright format, relatively rare in landscape painting, and the unconventional perspective, which divides the surface of the painting evenly between sky and field, reveal van Gogh’s fascination with Japanese art and its influence on his work in Paris. The colored woodblock prints of artists such as Hokusai and Hiroshige had already captured the interest of the Impressionists, strengthening their resolve to free painting from mere representation. Japonisme—enthusiasm for Japanese art and culture—reached its peak in Paris in the 1880s. Ever more dealers stocked woodblock prints, and even department stores sold them at affordable prices; upon his arrival, van Gogh was able to rapidly amass a considerable collection. He exhibited a selection of his prints at the Café Tambourin in March 1887. “The exhibition of Japanese prints that I had at the Tambourin had quite an influence on Anquetin and Bernard,” he later wrote to Theo. Van Gogh, too, was under the spell, and that year he began to systematically incorporate Japanese motifs into his own work through copies and free interpretations of such prints. In doing so, he replaced the more subdued tonalities of the originals with bright colors intensified through complementary contrasts. Edge of a Wheat Field with Poppies, with its Asian-inspired asymmetrical composition and feather of a poplar tree, may be one of the earliest examples of how van Gogh carried the spatial considerations of Japanese prints into his own work.

Son inmensas extensiones de campos de trigo bajo cielos turbulentos, y yo me propuse intentar expresar tristeza, una extrema soledad.

Si bien estos grabados podrían haber sido el ímpetu para las composiciones planas y dinámicas que creó en París, Van Gogh también miró a Japón como modelo para su ideal de una colonia de pintores, donde los artistas podían superar la envidia y la rivalidad para trabajar en forma cooperativa. Él creía que podría encontrar una versión de este Japón utópico en la región del Midi en el sur de Francia. Después de dos años en París, van Gogh partió hacia Arles en la primavera de 1888, y escribió a Theo: “Mira, amamos la pintura japonesa, hemos vivido su influencia —todos los impresionistas tienen eso en común— y por qué no irnos a Japón, en otras palabras, ¿al equivalente de Japón, al sur? Así que creo que, después de todo, el futuro del nuevo arte todavía está en el sur”.

El campo maduro bajo un cielo nublado de verano se convertiría en un motivo dominante en la obra de van Gogh durante sus años en las ciudades sureñas de Arles y Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, y más tarde en Auvers. El pequeño Campo de trigo de los alrededores de París es la primera representación de este motivo: un campo vacío a cielo abierto, sin campesinos ni ganado. Él reinterpretó la idea en una enorme variedad de pinturas, sondeando los límites de la perspectiva, la composición y el color. Para van Gogh el campo era una metáfora abierta y de múltiples capas. Poco antes de su muerte, en una carta a Theo y su esposa, Johanna, Vincent escribió sobre sus imágenes: “Son inmensas extensiones de campos de trigo bajo cielos turbulentos, y yo me propuse intentar expresar tristeza, extrema soledad”.

Este intento de plasmar el interior de la vida emocional del individuo a través del arte —una noción que ni siquiera se les habría ocurrido a los impresionistas— marca la transición de la postura positivista del impresionismo a la subjetividad absoluta de los expresionistas. Una nueva era había comenzado.