Frans Snyders

South Netherlandish, 1579–1657

A Pantry with Game

About 1640

Oil paint on canvas

The Phoebus Foundation, Antwerp

Image © The Phoebus Foundation, Antwerp

The Southern Netherlands—better known today as Flanders—was home to revolutionary artists. These extraordinary painters found new ways to depict reality, portray humanity, and tell stories that continue to resonate with viewers today.

Home to Europe’s intellectual and business elite, cities such as Bruges, Ghent, and Antwerp were the New York, Hong Kong, and Silicon Valley of the Renaissance. Antwerp, on the river Scheldt, was the most important port in northern Europe and the strategic hub for trade and finance.

The visual arts thrived in this dynamic and flourishing environment, resulting in new artistic genres and styles and a fresh approach toward images. The artworks in this exhibition open a doorway into the past, telling the story of enterprising townspeople, prosperous cities, and an ever-developing society. They also detail stories about dreams and ambitions, fears and desires, and what it means to be human.

100. Director’s Introduction

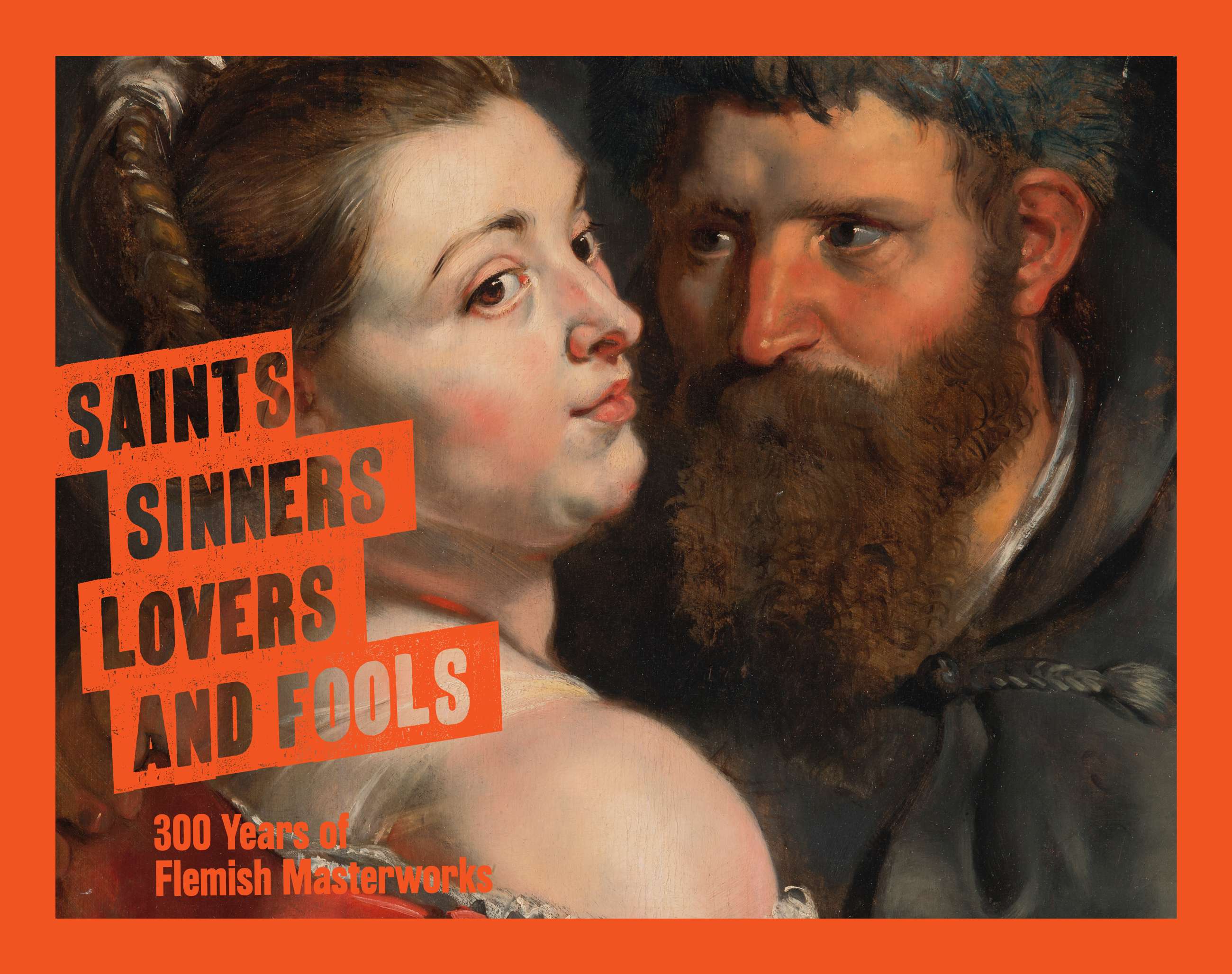

Christoph Heinrich: Hello, I'm Christoph Heinrich, Director of the Denver Art Museum. I'd like to welcome you to our special exhibition, Saints, Sinners, Lovers and Fools, 300 Years of Flemish Masterworks.

These artworks transport us back hundreds of years to Flanders, a slice of Europe south of the Netherlands in Northern Belgium.

By the 1400s, Flanders had become the financial powerhouse of Europe with global trading connections. Its cities were filled with artists working for wealthy patrons, eager to display their status and interests. Their art ranged from pious religious images to grand portraits, scenes from everyday life and stories from mythology. They also depicted nature and the latest scientific advances, all treated with a sense of realism and detail that marked a radical change in European art.

On your audio journey into this vivid bustling world, you'll hear from Dr. Katharina Van Cauteren, Director of the Phoebus Foundation in Antwerp, Belgium, home to this marvelous art collection. Welcome to Flanders – or, Welkom in Vlaanderen!

God is in the Details

After the huge loss of life from the Black Death that came to Europe in 1348 and the Hundred Years’ War (1337–1453), life seemed fleeting and uncertain. Many turned to the Catholic Church with its promise of eternal salvation.

Christians had previously relied on priests and monks to guide them in their devotions, but the emerging middle and upper classes in prosperous cities took matters of faith into their own hands. They brought paintings, sculptures, and manuscripts into their homes to help them empathize with Jesus and his mother, the Virgin Mary. They now saw these holy figures as flesh-and-blood human beings in familiar, contemporary settings.

Because people believed that everything was created by God, every detail in these paintings was precisely depicted—whether a strawberry, a magpie, or a shiny ruby. While you could learn about the divine mysteries by exploring nature, you could also gaze intently at the paintings that depicted nature in all of its detail.

Follower of Hieronymus Bosch

South Netherlandish, about 1450–1516

Hell

About 1540–50

Oil paint on panel

The Phoebus Foundation, Antwerp

Image © The Phoebus Foundation, Antwerp

101. Follower of Hieronymus Bosch, Hell, c. 1540–1550

Narrator: This painting, made by a follower of Hieronymus Bosch, aimed to fascinate – and to act as a terrifying warning. Death was all around in 16th century Flanders. And for Christians, the certainty of the afterlife meant believing in both heaven … and hell.

This vision of hell is filled with smoking ruins and fiery pits. Over to the right, a sharp-beaked creature sitting on a baby’s wooden potty chair devours and excretes people guilty of avarice, or greed. To the left, demons punish tavern-goers who’ve indulged in cards and drinking. And above them, giant severed ears flanking a knife seem to crush and chop human bodies beneath.

Katharina Van Cauteren: I'm Katharina Van Cauteren, I'm the Director of the Phoebus Foundation.

During the Last Judgment, God would decide whether you would receive the golden ticket towards Heaven or whether you would eternally burn in Hell. So you see that there is an enormous amount of paintings like this rather creepy scene, produced to help remind you of all that.

What fascinates me most about this painting are the musical instruments in the center. And they're supposed to be a warning, because music - at least a non-religious kind - was considered very dangerous. It was the devil trying to make you lose control, while singing or dancing. And you know, if you dance cheek to cheek, who knows which other sins could follow.

Eternity is a long time, so better to believe in God and live your life virtuously, I guess.

Gerard David

South Netherlandish, 1450/60–1523

The Lamentation

About 1500

Oil paint on panel

The Phoebus Foundation, Antwerp

Image © The Phoebus Foundation, Antwerp

In this intimate depiction of the lamentation, or mourning, over the dead body of Christ, Gerard David imbues a common theme in Christian art with human emotion. Details such as the folds in Mary’s headdress and Christ’s fragile collarbone contribute to the scene’s realism. The extreme close-up of the figures’ faces invites the faithful into this somber moment. Originally a diptych (indicated by dents left by hinges on the frame’s edge), this painting would have been used in private devotion.

Master of the Prado Adoration

South Netherlandish, active about 1475–1500

Saint Anthony Rebukes Archbishop Simon de Sully in Bourges

About 1450–75

Oil paint on panel

The Phoebus Foundation, Antwerp

Image © The Phoebus Foundation, Antwerp

102. Master of the Prado Adoration, St Anthony of Padua Rebuking Archbishop Simon de Sully at the Synod of Bourges, c. 1450-75

Narrator: Dressed in a brown monk’s habit, St Anthony has rebuked some French bishops for their love of magnificence. One of them kneels, asking forgiveness. Tears run down his wrinkled cheeks – a detail intended to engage a viewer’s own emotions.

Katharina Van Cauteren: And the theory is once again, from a medieval point of view, that if you want to go to Heaven, the best thing you can do is try to empathize, sympathize with the saints you see in pictures like this one.

Narrator: The bishop’s tears are just one element of the painting that sparkle and gleam. In medieval Christian culture, light symbolized God himself -

Katharina Van Cauteren: - which is why a painter like this pays so much attention to it. And if you look at this painting, you should see how the light falls through the windows, how it softly folds the fabrics with shadows, how it reflects in the gemstones and glistens in the gold.

What's interesting is that Flemish artists invented a completely new technique, which allowed them to catch the light and paint with this amount of detail. They no longer mixed pigment with egg, which was traditionally the way to make paint, but they started mixing pigment with linseed oil and that allowed them to paint in very translucent layers. So the picture almost seems to glow from within, as if it is literally lit by divine light.

Pieter Coecke van Aelst

South Netherlandish, 1502–1550

Triptych with the Adoration of the Magi

About 1530–40

Oil paint on panel

The Phoebus Foundation, Antwerp

Image © The Phoebus Foundation, Antwerp

Three kings journey from the East, following a guiding star, to bear gifts to the infant Christ. The biblical story of the magi is scant on details, but medieval Europeans numbered and named them, calling one Balthazar. Traditionally shown as white, by the late 1400s Balthazar began to be depicted as a young Black African ruler bearing the gift of myrrh.

Around this time, the Portuguese began trading enslaved people and goods from Benin, and they chose Antwerp as their principal port. Although foreign visitors could hold Black African slaves, slavery had no legal status in Antwerp. The free Black population was small, and often Flemish artists used the same Black models for their work.

103. Pieter Coecke Van Aelst, A Triptych: The Adoration of the Magi, c.1530-1540

Narrator: A triptych, or three-part altarpiece, symbolized the Holy Trinity: God the Father, Christ, and the Holy Spirit. Its side panels could be closed like doors over the central scene – their reverse surfaces usually featured paintings too. Opened up on holy feast days, the altarpiece was a revelation, a glory to behold.

Once, altarpieces were only seen in churches.

Katharina Van Cauteren: But now we're early 16th century, the citizens of the Southern Netherlands are becoming richer and richer, so they have big houses with lots of walls - and they can use a bit of decoration. And if that decoration can help you go to Heaven, all the better!

Narrator: The altarpiece shows the three Magi, or wise men, and the Christ child. It was made in Antwerp, which by the early 1500s, was among the most important European centers of trade - and art production.

Katharina Van Cauteren: There’s this Italian who goes to Antwerp, and he literally writes down that in Antwerp, there are more painters than bakers.

Narrator: The theme of the Magi with their exotic gifts was one of the most popular subjects among successful merchants, who traded in goods from afar. And in fact, religious paintings were among the first artworks that artists made on speculation for the market, rather than as one-off, custom pieces.

Katharina Van Cauteren: They think, if I paint this popular subject, someone will buy it you almost get this kind of supermarket for art. It was a trade, and you had to earn money from it.

Hans Memling and Workshop

South Netherlandish, 1430/40–1494

The Nativity

About 1480

Oil paint on panel

The Phoebus Foundation, Antwerp

Image © The Phoebus Foundation, Antwerp

If God created everything, from the tiniest buttercup to the tallest tree, then every part of creation helped the believer understand divine mysteries. In this Nativity scene, Hans Memling describes every detail with precision. As a late-medieval Christian, you were supposed to let your gaze slowly wander across the scene and reflect on each element. Using the new medium of oil painting, Memling placed one thin layer of paint on top of another, resulting in glowing colors, suggestive of divine light.

Master of Frankfurt and Workshop

South Netherlandish, 1460–1515/25

The Adoration of the Magi with Emperor Frederick III and Emperor Maximilian

About 1510–20

Oil paint on panel

The Phoebus Foundation, Antwerp

Image © The Phoebus Foundation, Antwerp

Contemporary viewers would have recognized the portrait of the reigning emperor, Maximilian of Austria, on the right-hand panel. He has a striking aquiline nose and white hair, and he wears on his chest the Burgundian Order of the Golden Fleece. Maximilian’s father, the deceased Emperor Frederick III of Habsburg, kneels in the central panel. Confident in their proximity to God, rulers often included themselves in sacred images, assuming the roles, in this case, of the magi offering gifts to the infant Jesus.

Saints, Sinners, Lovers, and Fools: 300 Years of Flemish Masterworks is co-organized by the Denver Art Museum and The Phoebus Foundation, Antwerp (Belgium). It is presented by the Birnbaum Social Discourse Project. Support is provided by the Tom Taplin Jr. and Ted Taplin Endowment, Keith and Kathie Finger, Lisë Gander and Andy Main, the Kristin and Charles Lohmiller Exhibitions Fund, the Samuel H. Kress Foundation, Christie's, the donors to the Annual Fund Leadership Campaign, and the residents who support the Scientific and Cultural Facilities District (SCFD). This exhibition is supported by an indemnity from the Federal Council on the Arts and the Humanities. Promotional support is provided by 5280 Magazine and CBS Colorado.