Introduction

Gerald Cassidy

Cui Bono?

about 1911

Oil paint on canvas

93 1/2 × 48 in.

Collection of the New Mexico Museum of Art: Gift of Gerald Cassidy, 1915 (282.23P). Photo by Blair Clark.

During the 1800s, Euro-Americans described, understood, and represented the American West as a place of cultural, religious, and geographical wonder, its own kind of “Orient.” Because of the close cultural and artistic connections between France and the United States, French Orientalism—an influential artistic style rooted in the infatuation with and fictions about Arab and Islamic cultures—permeated American art, design, music, literature, and entertainment. A shared context of colonial expansion—France into Algeria and the United States into the West—reinforced the popularity of Orientalizing motifs that artists used to depict the American West.

Like the colonial histories of France and the United States, these artworks are complicated. Composed from memory, imagination, and observation, they present a powerful visual authority that frequently obscures their nature as constructed objects. Often, we as viewers might see fictitious or stereotypical imagery as factual, which obscures and misrepresents the diversity of Indigenous communities around the globe. Is it possible to disentangle fact from fiction? How can we cultivate a critical eye in the face of beauty, simultaneously holding multiple, contradictory thoughts and feelings as we consider the impact of this colonial legacy?

This exhibition presents opportunities to consider and grapple with these questions as it reinserts western American art into its transatlantic context.

Framing French Orientalism

Coined in Europe, the word “Orient” comes from the Latin oriens for “east” and referred to places and people in North Africa, Turkey, the Mediterranean Basin, and much of the Islamic world, extending into all of Asia. Although Europeans had been fascinated by these places for centuries, Napoléon Bonaparte’s brief occupation of Egypt in the late 1700s inspired a renewed interest, resulting in the accumulation of preconceptions and stereotypes about North Africa reflected in many aspects of French culture.

Artworks produced by French artists during the 1800s inspired by North Africa and the greater Islamic world are often referred to as French Orientalism. The creation of these artworks paralleled French colonial expansion into Algeria beginning in the 1830s. The pervasiveness of Orientalist imagery, reflected in many aspects of French culture including the arts, literature, and opera, normalized generalized ideas about North Africa, often obscuring the effects of colonization. This gallery presents a variety of emotive, realistic, fantastical, and subjective representations of many “Orients” and sets the stage for how American artists would take up similar themes and techniques when depicting the West.

Luc Olivier Merson

Cleopatra Embarking on the Nile

late 1800s

46 × 65 in.

Collection of Dr. Richard Cohn and Mrs. Susan Cooper. Photography by Christina Jackson, courtesy Denver Art Museum

French Orientalism spans a range of fantastical imagery, including imagined history paintings such as this Egyptian spectacle. Luc-Olivier Merson’s interest in Egyptian history reflects the ongoing popularity of “Egyptomania” in the late 1800s inspired by Napoléon’s earlier attempts to colonize that country. Many artists, like Merson, did not travel to North Africa, finding ready inspiration in the widespread diffusion of Orientalist artworks and subjects.

Eugène Fromentin

An Encampment in the Atlas Mountains

about 1865. Oil paint on canvas

41 5/16 x 56 7/16 in.

The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore: Acquired by William T. Walters, between 1878 and 1884. 37.195

Eugène Fromentin traveled to Algeria three times between 1846 and 1853, ultimately publishing two books and creating many paintings about his experiences there. While his artworks are rooted in first-person observation, they are mediated by his imagination, his technique, and the preferences of his European and American clientele. Fromentin’s interest in equestrian cultures and vast landscapes, seen here, anticipates later representations of the cultures and geographies of the American West.

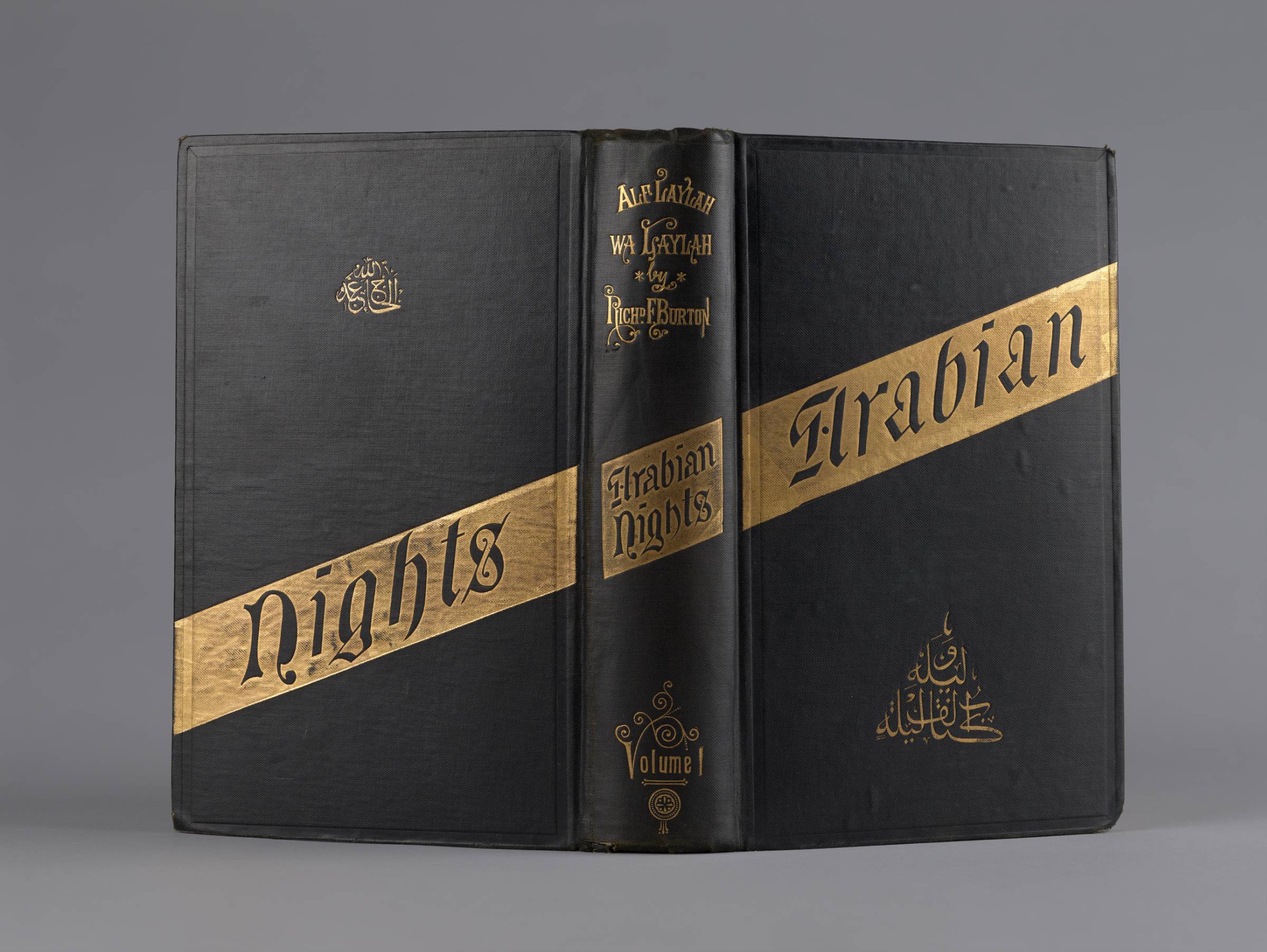

A plain and literal translation of the Arabian nights' entertainments by Richard F. Burton, 1898. Book. Lent by Denver Public Library, Western History and Genealogy Department, CA398.3 A658bd v.1. Photography by Christina Jackson, courtesy Denver Art Museum

A collection of stories from cultures in Egypt, Persia, Mesopotamia, and neighboring regions, One Thousand and One Nights (also known as The Arabian Nights) was first published in French and English during the early 1700s. Its sensational storytelling, wide-ranging adventures, and memorable characters made it one of the most popular books in Europe and the United States into the 1900s. Because of its popularity, it had a broad, and sometimes misleading, influence on perspectives of the Arab world.

Charles-Émile-Hippolyte Lecomte-Vernet

A Jewess of Morocco: Costume de Fête

1868

Oil paint on canvas

50 ¾ x 34 ¼ in.

On loan from Chrysler Museum of Art, Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr. 71.2059

During the 1800s and early 1900s, the Moroccan Jewish community numbered in the hundreds of thousands. For visiting artists, Jewish female models were often more accessible than their Muslim counterparts. Here, Charles Émile Hippolyte Lecomte-Vernet paints an unnamed woman dressed in her finest attire, called a kiswa al-kabira. By presenting her as confident but also sensually alluring, he hints at contradictory attitudes of the period that both respected and fetishized her culture.

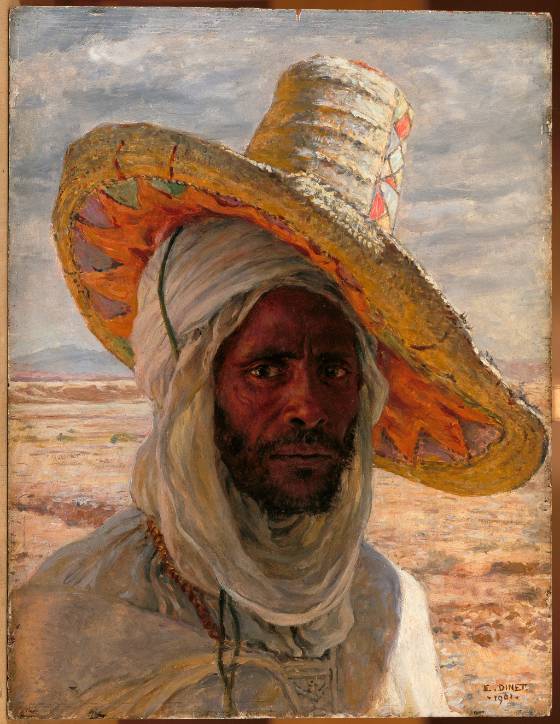

Alphonse-Étienne Dinet

Man in a Large Hat (Homme au Grand Chapeau)

1901

Oil paint on canvas

15¼ × 10½ in

Musée d'Orsay and Cité nationale de l'histoire et de l'immigration, Paris. © RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, NY. Photograph by Daniel Arnaudet

Born Alphonse-Étienne Dinet, this French artist ultimately moved to Algeria and converted to Islam, changing his first name to Nasreddine. His psychologically poignant portrait of this man may highlight his respect for Algerian people and culture, but at the same time, his nearby portrait of a young girl who flirtatiously pulls her veil across her face ventures into the problematic trope of the youthful seductress.

Community Voices

Focus group participants often pointed out the challenge of picking apart fact and fiction in these artworks:

Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant

In the Sultan's Palace

date unknown

Oil paint on canvas

26 × 19½ in. (66.0 × 49.5 cm)

Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Elmer Sandberg in honor of Mr. and Mrs. Henry H. Robinson, from the Permanent Collection of the Utah Museum of Fine Arts, University of Utah, UMFA1973.081.001

How can we tell what is based on fantasy in these paintings? I noticed the rug here. My father is from Afghanistan, and there’s a real appreciation for rugs and that kind of art in the culture. That detail makes me think of something ‘authentic,’ but this is fantasy. How will visitors think about the difference between fact and fantasy?

Some focus group participants highlighted artworks that have a strong sense of individuality:

John Singer Sargent

Egyptian Woman

1890–91

Oil paint on canvas

25½ × 21 in. (64.8 × 53.3 cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art: Gift of Mrs. Francis Ormond, 1950, 50.130.21. Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

I am from Egypt, and for me, this is one of the few images, or portrayals, in the exhibition that doesn’t seem obviously filtered through an Orientalist imagination. Even the veil that she’s wearing—it’s not used either to objectify her in a sexual way or to demonize her. There’s an element of strength and determination here.

Scholarly consultants often pointed out notable absences in artworks:

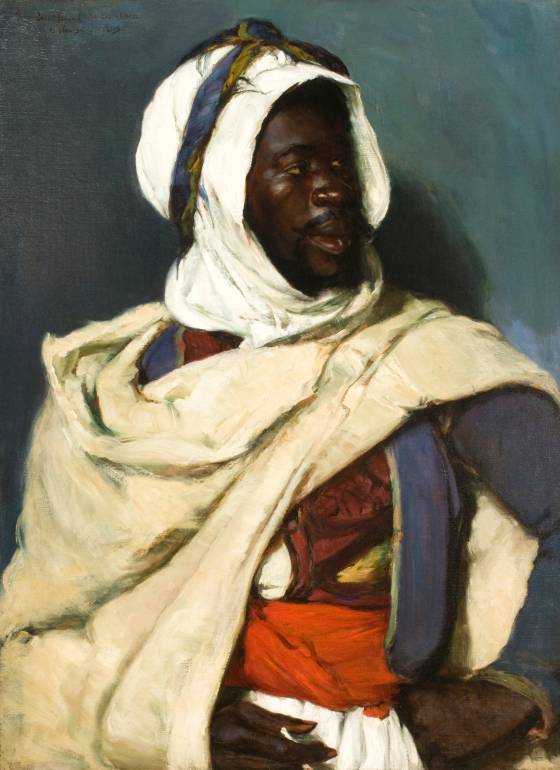

Elizabeth Nourse,

Moorish Prince (Head of an Algerian)

1897

Oil paint on canvas

32 × 23¾ in. (81.3 × 60.3 cm)

New Britain Museum of American Art: Harriet Russell Stanley Fund and through exchange, 1981.68

Blackness is often present in French Orientalist art, but rarely appears in art of the American West. I find it illuminating to think of blackness as a present absence in western American art, an escape by white artists into an imagined world devoid of blackness and its reckonings.

Frederic Arthur Bridgman

An Oriental Beauty

late 1800s

Oil paint on canvas

26 x 32 in

Dahesh Museum of Art, New York. 2012.16. © Dahesh Museum of Art, New York/Bridgeman Images

Charles Marion Russell

Keeoma #1

1896

Oil paint on academy board

18½ × 24½ in

Private collection. Photo courtesy of the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

The odalisque—a frequent motif in Orientalist art—is a woman in a female-only domestic setting, or harem. Often, her reclining pose and direct gaze reinforce assumptions about her sexual availability. From the colonizers’ perspective, she may present as an enticing symbol of people and lands to be conquered. This stereotype denies the multifaceted and complex roles of women by objectifying them as exotic commodities. In North America, some artists used this motif to represent Indigenous women. Such sexualized representations play a part in the ongoing crimes against missing and murdered Indigenous women, girls, and Two-Spirit (those who identify as having both masculine and feminine spirits) people.

Edward C. Moore for Tiffany and Co.

Indian coffeepot

about 1874

Sterling silver

10¼ × 6½ × 4¾ in

Dallas Museum of Art: Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Jay Gillette by exchange, Marie and John Houser Chiles, Mr. and Mrs. D. A. Berg, and Dr. and Mrs. Kenneth M. Hamlett, Jr., 1990.186. Image courtesy Dallas Museum of Art

Unknown artist, Egypt

Tray

about 1300–50

Brass inlaid with silver

2 × 18½ in. dia.

Metropolitan Museum of Art: Edward C. Moore Collection, Bequest of Edward C. Moore, 1891, 91.1532. Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Beginning in the mid-1800s, decorative arts from North Africa and the greater Islamic world appeared more frequently in European and American markets. Edward C. Moore, the first chief designer for the American jewelry and silver firm Tiffany & Co., used motifs from his own collection of global arts, including the Egyptian tray on display nearby, to create hybrid designs that would play a role in the development of a signature style that Moore considered distinctively American. Today, such visual fusions raise questions about the line between inspiration and appropriation.

Near East to Far West: Fictions of French and American Colonialism is organized by the Denver Art Museum. It has been made possible in part by a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities: Democracy demands wisdom. Research for this exhibition was supported by the Terra Foundation for American Art. It is presented with generous support from Keith and Kathie Finger, the Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation, Sotheby's, the donors to the Annual Fund Leadership Campaign, and the residents who support the Scientific and Cultural Facilities District (SCFD). Promotional support is provided by 5280 Magazine and CBS Colorado.