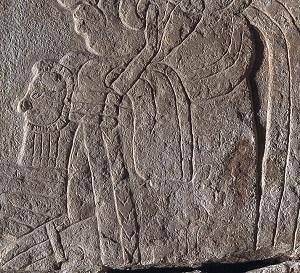

Stela with Image of Standing Ruler Burning Offerings

Maya peoples have lived in what we now call Central America for at least three-thousand years. Their territory included parts of present-day Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, El Salvador, and Honduras. Archeologists divide the ancient Maya civilization into three major time periods: Preclassic Maya (1500 B.C.–A.D. 250); Classic Maya (A.D. 250–900); and Post Classic Maya (A.D. 900–1500).

This wall panel was created during the Classic Period, which is considered the high point of Maya culture. The Classic Maya built cities with palaces, pyramids and temples to honor their gods, and made works of art in a variety of media. They are well known for their sophisticated hieroglyphic writing system, a number system that included the concept of zero, and a calendar for recording both historical and mythological dates. Expert astronomers, the Maya observed the movements of the planets and accurately predicted eclipses.

Maya artists were specialists who produced ceramics, stone sculptures, and jewelry of jade and shell. The Maya word for artist is its’at, which means “wise man” or “sage.” Maya scribes carved inscriptions in stone, and painted them on ceramics and in books made of fig bark paper. Hieroglyphic inscriptions recorded dynastic histories, including births, deaths, and marriages. Military victories and religious ceremonies were also recorded. Like artists today, some Maya artists even signed their works.

This carved limestone slab was a wall panel from a Maya palace or administrative structure. Maya rulers commissioned stone monuments to glorify their ancestry and to proclaim their wealth, taste, military victories, and spiritual power. The image shows a Maya ruler performing an incense scattering ritual that celebrates the end of a 10 year period called a lahuntun. Along the left side of the panel, and across the top are individual signs called glyphs. The glyphs represent words or syllables that can be combined to form words. The glyphs on this panel show the date December 2, A.D. 780.

We know of two other stone carvings of this ruler, one in a private collection in Mexico, and the other in an Australian museum. These carvings suggest that he was an important ruler in his day. In both carvings, the man’s distinctive facial features are clearly identifiable and he is shown grasping prisoners by the hair.

Details

Glyphs

The hieroglyphic text forms a wall and ceiling around the figure, suggesting that he is standing inside a building. The Maya developed their own system of writing, which archeologists consider to be the most sophisticated ever developed in the Americas. The written language consists of hundreds of individual signs, called glyphs, which are paired in columns that read from left to right and top to bottom. The Maya writing system allowed room for artistic expression, so Maya glyphs are often quite elaborate. The first nine glyphs in this carving record the date; the tenth glyph is the verb; and the remaining thirteen glyphs describe the ruler. From the glyphs we know that the ruler was the master of a captive named Yax-ik’nal, and that he captured fourteen other prisoners, which suggests that he was very successful in battle. The glyphs also tell us that the ruler was at least 41 years old, and no older than 60, at the time the stela was made.

Jeweled Headband

The man in the monument can be identified as a ruler because he wears a jeweled headband around his forehead called a sac hunal, which means “resplendent one.” It is similar to a crown and would have been tied around the ruler’s head when he came to power. In the center of the headband is the head of a deity, which was usually carved in jade. The deity wears a long, three-pointed cap and is nicknamed the “jester god.”

Ornaments

The ruler wears a jade ornament in the shape of a head on his chest. Long quetzal feathers decorated with jade beads fall down his back. Both of these ornaments are signs of his powerful status.

Distinctive Facial Markings

Notice the figure’s heavily lidded eye, the swirling line on his nose that could be a facial scar, and jade bead ornaments on his nose.

Headdress

On top of the ruler’s headband sits a jaguar head. Above that is the glyph ak’bal, which means “darkness.” Smoke or fire rises out of the ak’bal glyph.

Clothing

The man wears a knotted scarf around his neck and a long cape decorated with three human eyes. Both of these are part of the special clothing the Maya wore when performing sacrificial rituals.

Incense Bag

In this ritual, the ruler is shown scattering incense. His left hand holds a long bag containing the incense, and his right hand is in the scattering gesture. At his feet is a large basket containing long strips of paper and a small tied bundle.

Empty Space

The empty space between the figure and the glyphs emphasizes the outline of the figure, particularly in the areas around his face and headdress.

More Resources

Websites

Nova Online: Lost King of the Maya

A companion website to the film “Lost King of the Maya,” that includes video clips about Copan, accounts of discovering an ancient Maya city, a map of the Maya world, an interactive feature reading Maya hieroglyphs, and other resources.

Living Maya Time

An interactive website from the Smithsonian Museum of the American Indian featuring Mayan astronomy and agriculture.

Maya Ruins

A web resource containing a photographic tour of many different Maya sites.

DIG! The Maya Project

Kids are the archaeologists in this interactive game from the Dallas Museum of Art. They can "intern" with an archaeologist, dig for Mayan objects, record their finds in a journal, and play games. Recommended for ages 10 and up.

Books

Foster, Lynn V. Handbook to Life in the Ancient Maya World. United States: Facts on File, Inc., 2002.

A comprehensive guide to the Maya culture that describes their evolution and time periods, geography, society and government, warfare, religion, funerary ritual, architecture, astronomy, economy and daily life.

Greene, Merle. Ancient Maya Relief Sculpture. New York: Museum of Primitive Art, 1967.

This book contains numerous rubbings of Maya relief sculpture, each accompanied by a description of the work’s content.

Houston, S.D. Reading the Past, Maya Glyphs. California: University of California Press, 1989.

An informative text about the discovery and deciphering of the Maya’s glyph writing system: its origins, development, media usage and structure, accompanied by a sample text.

Laughton, Timothy. The Maya, Life, Myth and Art. New York: Stewart, Tabori and Chang, 1998.

A look into Maya gods, rituals, myth and life, accompanied by wonderful photographic examples of their art.

Children's Books

Day, Nancy. Your Travel Guide to: Ancient Mayan Civilization. Minneapolis: Runestone Press, 2001.

A fun book for ages 9-12, formatted as a travel guide for visitors to this culture and time period. Includes information such as how to get around, where to stay, and where to eat, among many other engaging travel activities.

Dupre, Judith. The Mouse Bride, A Mayan Folktale. United States: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1993.

A wonderfully illustrated book for ages 4-8 that retells a classic Maya folktale.

Perl, Lila. The Ancient Maya. United States: Franklin Watts, 2005.

For ages 9-12, this book describes Maya culture, occupations, religion and much more.

Roberts, Timothy R. Gods of the Maya, Aztecs and Incas. New York: Michael Friedman Publishing Group, Inc., 1996.

A book about the gods of these three cultures, with stories about them.

Funding for object education resources provided by a grant from the Morgridge Family Foundation. Additional funding provided by the William Randolph Hearst Endowment for Education Programs, and Xcel Energy Foundation. We thank our colleagues at the University of Denver Morgridge College of Education.

The images on this page are intended for classroom use only and may not be reproduced for other reasons without the permission of the Denver Art Museum. This object may not currently be on display at the museum.