Students will learn about ideas of order, chaos, pattern, and variation in poetry. They will then use Waddell’s Motherwell’s Angus to discuss these ideas. The painting will serve as inspiration for the students as they write both traditional and free form poems.

Students will be able to:

- explain what is meant by order, chaos, pattern, and variation in poetry;

- discuss how Motherwell’s Angus evokes a sense of order and/or chaos;

- feel comfortable taking creative risks to write both a traditional and free form poem about Motherwell’s Angus; and

- work with peers to edit and refine poems.

Lesson

- Preparation: Read the About the Art section on Motherwell’s Angus, in particular the “Details” information. Select poems to use for the Warm-up and prepare a mini-lecture on order, chaos, pattern, and variation in poetry, using resources from the Owl Purdue Online Writing Lab.

- Warm-up: Have the students read two different poems, one written using a classical form, and one in free verse. (Owl Purdue has a great description of the difference here.)

- Have students talk with a partner about their impressions after they read each poem, as well as how each makes them feel. Call on volunteers to share some of their ideas. Lead a discussion on the difference between order and chaos, and pattern and variation. Can they find any instances of those four ideas in the poems? Where? How do these four literary techniques evoke different responses within readers?

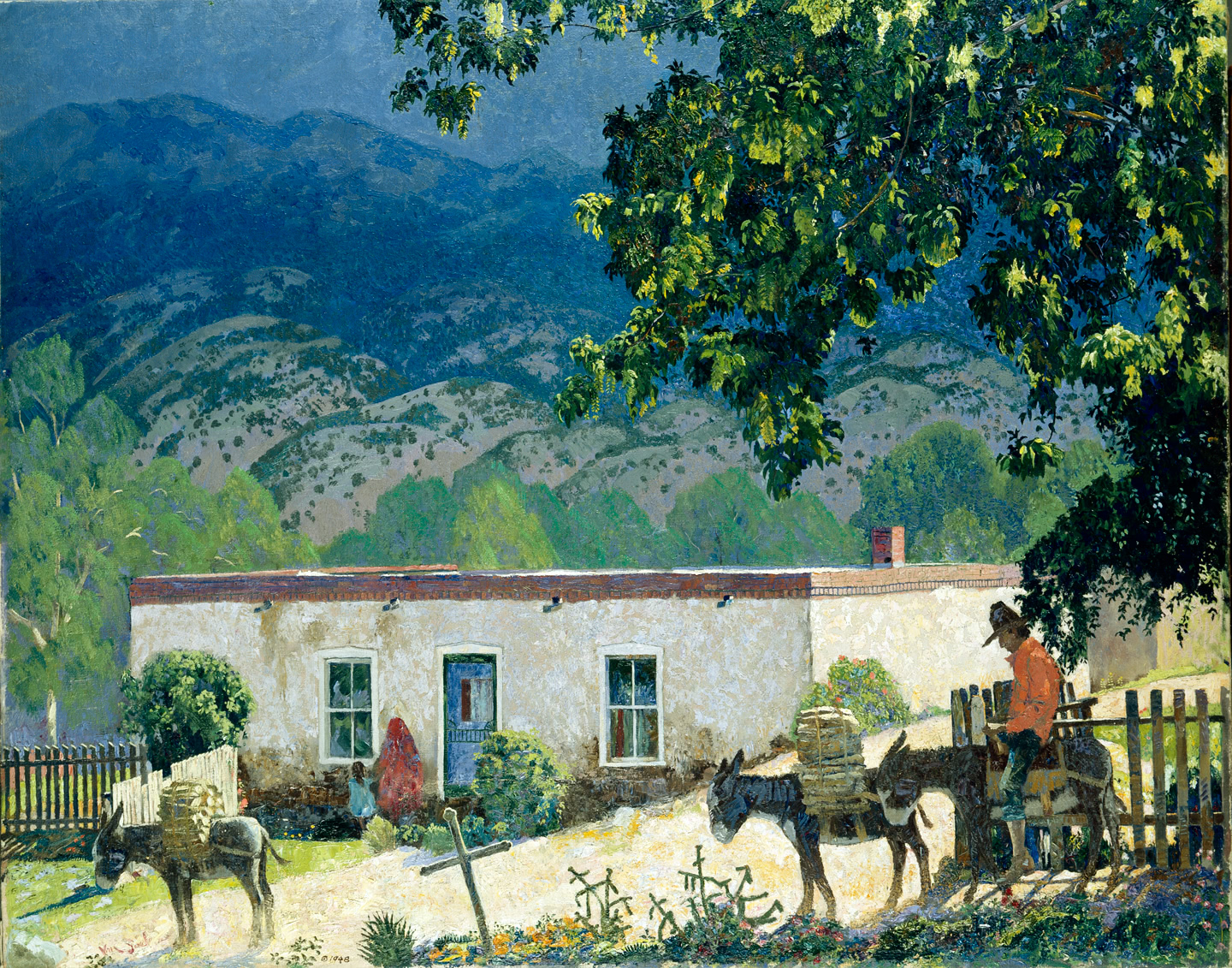

- Show students Motherwell’s Angus. Ask students if they feel the painting evokes a sense of order or chaos. Why? How? What specific visual aspects of the painting can they identify that illustrate their opinion?

- Share with students information from the About the Art section that explains why the painting appears more free form. Ask students their thoughts on this point: do they agree or disagree? Why might Waddell have chosen a more free form composition for this painting? How would the painting convey a different tone if it were more structured?

- Have the students write two poems inspired by the painting. One should follow a traditional poetry pattern, such as a sonnet. The other should be free form. Encourage them to include a visual free form element if they have never experimented with the poetry form.

- Have students work with a partner to peer edit their poems. When everyone is finished, ask students to neatly write out their favorite of the two and post them on the wall for a “gallery” walk so students can read each other’s poems.

Materials

- Paper and pencils for each student

- About the Art section on Motherwell’s Angus

- Color copies of Motherwell’s Angus for students to share, or the ability to project the image onto a wall or screen

Standards

- Visual Arts

- Observe and Learn to Comprehend

- Relate and Connect to Transfer

- Envision and Critique to Reflect

- Language Arts

- Oral Expression and Listening

- Writing and Composition

- Reading for All Purposes

- Invention

- Self-Direction

Motherwell's Angus

- Theodore Waddell, American, 1941-

- Born: Montana

Theodore Waddell is a third-generation Montanan who has deep roots in both the West and American art. His pioneer grandmother moved west in a covered wagon, and his grandfather was an acquaintance of notable western artist Charles Russell. Born in Billings, Montana, Waddell grew up in Laurel, a small railroad town on the Northern Pacific line about 15 miles west of his birthplace. His father painted railroad boxcars and enjoyed working on paint-by-numbers during his time off. One of Waddell’s earliest memories is the smell of oil paint on his father’s clothes, and his love of the medium continues today.

Although Waddell set off for Eastern Montana College (now Montana State University-Billings) with an interest in architecture, he flunked a math test which derailed his plan of study. Instead, he enrolled in a studio art class offered by western landscape artist Isabelle Johnson, a decision that he cites as one of the most important and influential of his career. Within a month of meeting Johnson, Waddell decided, “I didn’t want to be alive and not make art.”

Waddell spent a year in New York City in the early 1960s, attending art classes at the Brooklyn Museum Art School and immersing himself in the work of abstract expressionism that artists like Jackson Pollock, Robert Motherwell, and Clyfford Still had developed in the 1950s. The energetic splashes, drips, and fields of oil paint on their canvases added to his lifelong love of the medium.

Despite the excitement of New York, home beckoned, and Waddell returned west to complete his degrees in studio art and education. He taught for several years at the University of Montana, and from 1976 to 1996, he settled down as a rancher, making art alongside his ranching duties. He would rise out of bed at 3:30 a.m. and paint until 8:00 a.m., when his ranch work began. During the winter—calving season—he would check on the cows at 2:00 a.m. and stay up to paint!

Waddell feels a strong connection to his home, saying that “Montana has caused me to be who I am, and I love this place,” and “I have to be where I am to paint what I paint.” He also loves animals and has spent decades of his life surrounded by cattle, sheep, horses, dogs, and other furry friends. He sees the animals and landscapes that he paints as inextricably connected; the cattle “give a focus to the landscape that can’t be perceived any other way.”

Winter is one of Waddell’s favorite times to paint. In winter, the landscape changes quickly and the snow reflects colors of light that are rarely found naturally in other seasons. Waddell also recalls that winter was one of his most productive artistic seasons when he was a rancher. Though he did need to check on his livestock, his fields required less attention during winter, giving him more time to paint.

Waddell often titles his paintings in honor of artists who have inspired him. While living and studying in New York City in the early 1960s, abstract expressionist artist Robert Motherwell was Waddell’s “all-time favorite.” Waddell was drawn to the flattened surface, textured application of paint, and abstracted forms of Motherwell’s canvases. Waddell completed a total of 25 paintings of cows in homage to the artist. This canvas is #6 of the series. Other homages to artists include Monet’s Sheep and Vincent’s Angus (after Vincent van Gogh).

Details

Dark Spots

At first glance, the dark blotches of paint scattered across the canvas might not look like any recognizable form or figure. A closer look reveals the legs, heads, and torsos of cows emerging from and disappearing into the painted landscape. Waddell wasn’t interested in depicting individual animals—none of the cows have specific features, nor are they painted with any detail. Rather, he was interested in painting the impression of a cow.

Cool Colors

Waddell applied white, light blue, and lavender paint to the canvas to create the feeling and appearance of a cold winter landscape. These cool colors bleed into one another throughout the work and are visible up close.

Endless Landscape

The cold winter landscape covers the entire surface of the canvas. Without any horizon line or use of perspective, the winter prairie stretches as far as the eye can see. The expansive view also comes from a lack of a focal point, which encourages the eye to roam across the picture plane. The cows are scattered about asymmetrically, at times even coming to the edge of the canvas.

Blending of Paint

From afar, the black paint of the cows contrasts sharply with the white and pastel-colored paint that makes up the winter landscape. Up close, however, the black paint blends into the lighter colors with subtler gradations. This painting technique adds to the snowy, hazy feel of the image.

Thick Paint

Waddell uses masonry trowels and specially modified brushes originally intended to apply tar to roofs to create a heavy build-up of paint on the surface of the canvas. Some areas of paint are so thick that the texture looks like frosting!

Waddell feels that “there’s a magic to oil paint that is unsurpassed by any other medium or activity. The notion of loading a brush with a big dollop of paint is about as good as it gets. The sensation of developing a line or shape with this material is wonderful.”

Large Square

Motherwell’s Angus measures six feet square. Waddell likes to paint his works on large canvases, giving him plenty of room to play with his paints, and suggesting the vastness of the Montana landscape.

Funding for object education resources provided by a grant from the Morgridge Family Foundation. Additional funding provided by the William Randolph Hearst Endowment for Education Programs, and Xcel Energy Foundation. We thank our colleagues at the University of Denver Morgridge College of Education.

The images on this page are intended for classroom use only and may not be reproduced for other reasons without the permission of the Denver Art Museum. This object may not currently be on display at the museum.