Students will observe and discuss Daniel Sprick’s still-life painting Release Your Plans and comprise a list of questions they would like to ask the artist. They will then attend a mock press event as art critics, asking questions and jotting down notes for an art review they will write as homework.

Students will be able to:

- identify and describe details in a painting;

- conduct and take notes at a mock press event;

- write an art review based on their notes; and

- answer questions from Sprick’s point of view based on what they learn.

Lesson

Day 1

- Warm-up: Students are often asked to write stories and narratives. For this activity, introduce the concept of writing in a new way by inviting the students to write out the instructions for how to zip a zipper. Have them imagine they are writing for somebody who has never worn a jacket with a zipper before. They must be clear and concise.

- Before class, prepare slips of paper with questions from Sprick’s FAQ sheet.

- Show students Sprick’s painting Release Your Plans. Give students at least ten minutes to observe the painting and jot down notes on what they see, what the painting might be about, who the artist is, where the objects came from, what the painting reminds them of, etc.

- Explore what the artist chose to include in the painting by calling on students to identify which object stands out the most to them. What other objects did the students notice after observing the painting for awhile? Why might some of the objects be floating? Weave in information from the About the Art section when possible.

- Ask the students, “If you could change one thing about Sprick’s arrangement, what would it be?” Share the following paragraph from About the Art :

- “Sprick built this table specifically for use in still-life paintings. He wrapped it several times, adding more sheets underneath for bulk, and still isn’t sure he got it just right. He likes the psychological tension the string adds to the painting, but he still wonders sometimes, why wrap something up?”

- Explain to students that sometimes, even professional artists don’t know why they do something a certain way. It’s okay to look back at your art and want to change or add things.

- In small groups, instruct students to compile a list of questions they would like to ask the artist. Write their questions on the board (these will be used in the next lesson).

- Explain to the students that Sprick can’t come to the classroom to answer their questions, but the Denver Art Museum invited visitors to ask him questions and that you have his responses. From the slips of paper you prepared in advance, have them choose a question.

- Hold a mock press event, with you pretending to be Sprick and the students pretending to be art critics. Have them ask the questions they drew and, as you’re responding using the FAQ sheet, they should be jotting down notes.

- When all of the questions have been asked, explain to the students that after a press event, critics turn their notes into an art review. For homework, they need to write a review on Sprick. You may also want to bring examples of shorter reviews as examples for the students.

Day 2

- Begin by revisiting the students’ questions you wrote on the board during the previous lesson. Choose one question to answer as a class. Using what the students learned about Sprick from the previous lesson, have them each write a response to the question based on how they believe Sprick would answer.

- Invite the students to share their answers with the class and discuss their responses. How were the responses similar? How were they different? How do the responses reflect Sprick? Do the students look at Release Your Plans differently now that they know all about Sprick? What changed?

- Give students time to peer edit each others’ reviews and revise as needed. Encourage them to add even more details and mock quotations from Sprick.

Materials

- Pencils/pens and paper

- About the Art section on Release Your Plans

- One color copy of the painting for every four students, or the ability to project the image onto a wall or screen

- Sprick’s FAQ sheet

Standards

- Visual Arts

- Observe and Learn to Comprehend

- Relate and Connect to Transfer

- Language Arts

- Oral Expression and Listening

- Research and Reasoning

- Writing and Composition

- Reading for All Purposes

- Collaboration

- Critical Thinking & Reasoning

- Information Literacy

- Invention

- Self-Direction

Release Your Plans

- Daniel Sprick, American, b. 1953

- Born: Little Rock, AR

- Work Locations: Glenwood Springs, CO

Daniel Sprick was born in Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1953, and has lived off and on in Colorado since the age of five. He now lives and works in Glenwood Springs, Colorado, which gives him a “comfortable and predictable lifestyle that is right for a person to develop as an artist.”

Many of Sprick’s oil paintings, including Release Your Plans, feature an arrangement of objects set up in his studio. Some of his favorite objects show up in multiple works. He carefully selects and arranges the objects, making choices intuitively. “Mostly I paint things because I like the way things look,” says Sprick. “I have mountains of books on iconography, but iconography isn’t substantial enough. The thing has to resonate, have its own visual appeal. However, there could be some meaning in there that I don’t even know about—I’m not saying there is no meaning in there.”

While his style is very realistic, Sprick does make changes to what he sees before him, and he doesn’t limit himself to the laws of nature. He says, “I mostly see the world as a pretty good place. I guess that’s what I want to come though my work—something life affirming or some sense of well being, some optimism, some hope—even though I load it with portents of mortality and so forth. You know, I haven’t forgotten that those things exist, and I don’t think that the world is just a field of puppies romping in the daisies or anything, but it’s a good place, I just realize that there’s razor blades and cigarette butts, too.”

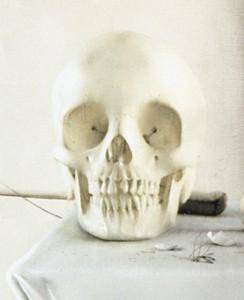

Sprick chose the objects in Release Your Plans simply because he likes the way they look. “That’s it. It’s not loaded with importance, it’s just that they satisfy me on some primitive level of the brain,” he says. He doesn’t like to look too hard for subject matter, because even a “cubic foot of the world contains the mysteries of the universe.” For Sprick, all kinds of things affect how a painting develops—“what’s in bloom outside at the time, what’s in the refrigerator.” The skull quickly became the focus in the painting, although he originally had something else in its place (an object that he eventually eliminated altogether). Sprick is drawn to paint bones because of how they look, saying, “I have a hard time leaving them alone because of their inherent beauty.” He tried to “play down the grim reaper a bit” by painting the skull the same color as the background so it wouldn’t stand out as much.

This piece took about four months to paint, and during that time Sprick worked on this painting only. He completed about 90% of it, however, in the first two months. Every square inch of the painting has to work for him. Sometimes he will spend up to a week working on just one part, a part that he thinks should have taken him just one day.

Details

Title

The title of this painting came from an interview Sprick heard on the radio while he was working on this painting. During a fundraiser, someone said “Listen to your destiny, and when it calls, release your plans.” This message is written on the piece of paper tacked on the wall behind the easel in the painting, and the words “Listen” and “Release Your Plans” are repeated on the bottle and the soup can.

Skull

The skull first belonged to his dad, who made dentures for a living (this one has a good set of teeth). Sprick finds the skull, as well as the leg bone on the floor, visually pleasing. He’s looked at bones so much that he doesn’t associate them with feelings of death the way others might. But he does handle them with reverence, conscious that they were once part of a human being.

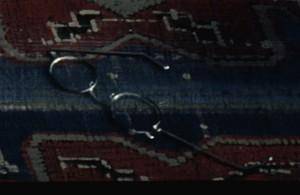

Glasses

Sprick thinks the glasses add a sense of story to the work, and he sees them as evidence of human frailty.

Kitchen Refuse

Sprick doesn’t have to go far to find things like eggshells, old cans, and broken bottles to paint. He likes to combine things that are beautiful with things that are not. There are usually visual qualities that appeal to him, like the sharp edge and bright white of an eggshell.

Broken Stuff

Sprick finds broken bottles and glasses especially interesting. He rescues things from the trash but says he’d never break something just to paint it.

Floating Objects

Sprick says that some objects end up floating because the support he was using (a clamp for a rose or a jar propping up a plate) didn’t look right in the layout of the painting. But he admits he also likes a bit of magic.

The Rug

How do you make a rug really look like a rug? By laying in the paint the same way the rug was made. Sprick’s brushstrokes followed the direction of the warp and weft (the lengthwise and crosswise threads) of the rug.

Shrouded Table

Sprick built this table specifically for use in still-life paintings. He wrapped it several times, adding more sheets underneath for bulk, and still isn’t sure he got it just right. He likes the psychological tension the string adds to the painting, but he still wonders sometimes, why wrap something up?

Cigarette Butts

Sprick says that eggshells, cigarette butts, kitchen refuse, and other debris are “testimonials to living.”

Dead Bugs

Look for the bugs on the table top. The artist actually keeps a box full of dead bugs and butterflies just to use in paintings.

Shades of White

To paint a large area with subtle shading, like the white wall, Sprick mixes all of the shades before he starts painting. He lays them out on his palette in an arrangement that reflects where they will go on in the painting. Look for shades of white that are warmer (have more yellow in them) and shades of white that are cooler (have more blue in them).

Funding for object education resources provided by a grant from the Morgridge Family Foundation. Additional funding provided by the William Randolph Hearst Endowment for Education Programs, and Xcel Energy Foundation. We thank our colleagues at the University of Denver Morgridge College of Education.

The images on this page are intended for classroom use only and may not be reproduced for other reasons without the permission of the Denver Art Museum. This object may not currently be on display at the museum.

![Carlos Frésquez installation, part of Cuatro [4]: A Series of Artist Interactions.](https://d26jxt5097u8sr.cloudfront.net/s3fs-public/Carlos%2520Fresquez-Cuatro%2520installation_360pixels_0.jpg)