Students will examine the artistic characteristics of the Olmec Seated Figure, learn about significant cultural beliefs in the Olmec civilization, and write a descriptive essay or creative short story featuring an alter ego.

Students will be able to:

- examine the artistic characteristics of the Olmec Seated Figure;

- explain the concept of an alter ego; and

- write a descriptive essay or creative short story featuring an alter ego.

Lesson

- Warm-up: Display or pass out copies of the Olmec Seated Figure and invite students to look carefully and share what they observe. What do they notice? How would they describe the body position of the figure? How would they describe the expression on the figure's face? What materials do they think were used to make the figure? How do they think the artist made the figure? What adjectives would they use to describe the figure? Does the figure remind them of any other art objects they have seen?

- Share with students that the figure was created in Mesoamerica between 1000 and 500 B.C. Show students where Mesoamerica was located on a world map. You can find several maps of Mesoamerica by going to Google Images and entering “Mesoamerica” in the search box.

- Explain to students that the Olmec believed that powerful individuals were able to transform into jaguar alter egos. Explain that an alter ego is a person's second self, or second personality. Invite the students to look at the figure’s expression again and notice how the shape of the mouth could be compared to a jaguar’s snarl.

- Ask students to think about the following question: What are some examples of individuals and their alter egos (e.g. Clark Kent and Superman)? Record their responses on a (interactive) whiteboard or piece of chart paper in the front of the classroom.

- Invite students to ponder the following question: If they had an alter ego, what would that alter ego be like? What would it look like? In what kinds of activities would their alter egos participate? When would they transform into their alter egos? As an option, the students could think of a powerful individual in history and create an alter ego for that person.

- Have the students write a brief descriptive essay or creative short story in which they provide a clear picture of both themselves (or a powerful individual in history) and their alter egos. Encourage students to illustrate their stories or essays if they would like to.

- When students are finished, invite them to share their written creations and display their assignments in the classroom.

Materials

- Lined paper and a pen or pencil for each student

- Map of the world, visible to all students in the classroom

- Internet access to Google Images for maps of Mesoamerica

- Copies of About the Art sheet on the Olmec Seated Figure (found at the end of the lesson plan) or student access to this part of Creativity Resource online

- One color copy of the figure for every four students, or the ability to project the image onto a wall or screen

Standards

- Language Arts

- Collaboration

- Critical Thinking & Reasoning

- Information Literacy

- Invention

- Self-Direction

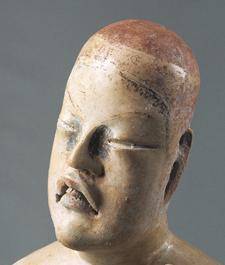

Seated Baby Figure

This figure was created by an Olmec [ole-mek] artist. The term Olmec refers to the pre-Columbian culture that flourished on the Gulf Coast of Mexico from 1400–500 BC, and to the style of art found throughout Mesoamerica during this period. Mesoamerica is defined by a group of cultural traits, including agriculture and a diet based on a triad of crops (maize, beans, and squash); the use of a 365-day solar calendar and a 260-day ritual calendar; the playing of a sacred ballgame; the construction of monumental public architecture; and a religion that emphasized blood sacrifice. The Olmec was Mesoamerica’s first civilization to embody all or most of these traits.

The artist who crafted this hollow earthenware figure modeled it from pinkish clay and covered it with a smooth white slip (a mixture of clay and water) to give it a skin-like look. The artist then applied red and black pigments to the head and face, possibly after the figure was fired (heated to harden the clay).

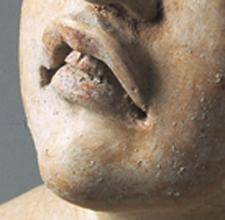

Figures like this one are called “babies” because of their large head proportions and often short, fleshy limbs. The faces on Olmec figurines are distinctive, with heavy eyelids and thick lips with down-turned corners. Some, like this one, have a jaguar-like mouth. Some scholars think that in Olmec belief, powerful individuals had jaguar alter egos and Olmec shamans (intermediaries between the human and spirit worlds) were able to transform themselves into jaguars. Called were-jaguars (like werewolves), these figures have snarling or crying mouths, are sexless, and suggest possible shamanic transformation of humans into animals. The purpose of these types of figures is unknown. In other Olmec depictions, supernatural baby-like figures are held on the laps or in the arms of sculptured Olmec rulers. The baby-like figures may have had an association with the natural elements such as earth or water.

Details

Relaxed Pose

The figure sits in a relaxed asymmetrical pose with the head slightly cocked.

Limbs

The limbs are soft, thick, rounded, and don’t reflect any anatomical reality of bones and muscle. The hands and feet are small and elegant.

Head

The head is an elongated oval with narrow eyes, a slender nose, and delicately outlined eyebrows and hairline. Red and black pigment heightens the features, perhaps to indicate the figure is wearing a helmet or other headdress.

Mouth

The mouth has strongly down-turned corners. This mouth shape has been compared to a jaguar’s snarl.

Funding for object education resources provided by a grant from the Morgridge Family Foundation. Additional funding provided by the William Randolph Hearst Endowment for Education Programs, and Xcel Energy Foundation. We thank our colleagues at the University of Denver Morgridge College of Education.

The images on this page are intended for classroom use only and may not be reproduced for other reasons without the permission of the Denver Art Museum. This object may not currently be on display at the museum.