New Territory: Landscape Photography Today on view at the Denver Art Museum from June 24, 2018 through September 16, 2018 presents over 100 works by 40 artists from around the world. The exhibition explores the expanding boundaries of landscape photography by featuring the work of contemporary artists who are reconsidering how to make a photograph and who use the traditional subject to reflect on our relationship with the landscape as well as our impact on it.

One of the earliest known photographs was made in 1826 by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce using a process he developed called heliography (‘sun-writing’). It took 8 hours. For the first 100+ years of the medium, though numerous processes were developed, photographs were essentially created by the reaction between chemical elements and light.

Since the rise of digital photography and with increasing technological advancements, the ways in which to make a photograph continue to grow. Many of the photographers on view in this exhibition have revived traditional ways of making a photograph and others have combined those methods with new approaches to the medium.

Here, I would like to focus on three artists in the show who work in collaboration with the landscape by incorporating natural materials—from the sky, the earth, and the sea—into their photographic process. Through their unique methods, they are not only literally connecting their image with the elements of the landscape that inspired it but are also echoing historic photographic processes of their predecessors.

Chris McCaw, Heliograph #77, 2015. Four unique gelatin silver paper negatives. Courtesy the David and Kathryn Birnbaum Collection.

Sun

Chris McCaw harnesses the intense power of the sun to play a part in the creation of his innovative photographs. He has built a custom large-format camera and routinely works with long exposures. His Heliograph series is a nod to the early images created by Niépce but uses different materials.

McCaw places photo paper directly into his cameras and through long exposure times is able to initiate a process called solarization, which reverses the darks and lights in the image. These long exposures also encourage the sun to scorch and at times burn through the paper, leaving a scar depicting the sun’s movement throughout the exposure. The resulting unique photographs are subtle dark landscapes beautifully marred by the sun.

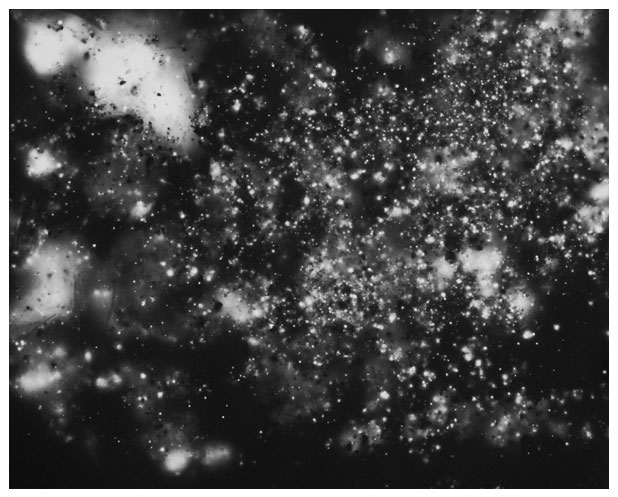

Shimpei Takeda, Trace #7, Nihonmatsu Castle, 2012. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy of the Artist. © Shimpei Takeda.

Earth

Shimpei Takeda is a Japanese photographer who explores ideas of abstraction in photography while also incorporating social commentary. The images from his Trace series evoke a starry sky but were made with contaminated soil. On March 11, 2011 a tsunami hit Japan killing thousands of people and destroying much of what lay in its path. In addition, this natural disaster caused a level 7 meltdown at Fukishima nuclear power plant.

In 2012, Takeda collected soil samples from locations where people still lived and worked. He specifically chose places that were related to both life and death such as temples, shrines, war sites, hospitals, his birthplace.

To create the images, Takeda used a camera-less method similar to the photogenic drawings first created by William Henry Fox Talbot in 1839 and the photograms of modernist photographers such as Man Ray and Laszlo Moholy-Nagy in the 1920s. However, instead of placing objects on light sensitive paper and exposing them to light to create images, Takeda experimented with how a photograph could be made without light. He placed the contaminated soil samples on a negative and encased it in a light-less box. The electromagnetic radiation of the contaminated soil exposed the negative in similar way that light would have. The prints created from these negatives make visible the dangerous, lingering effects of this event—traces of radiation that still remain in the soil.

Sea

Meghann Riepenhoff explores the possibilities of another early type of photograph, the cyanotype. The process was invented by Sir John Herschel in 1842 and historically most notably used by English botanist Ana Atkins to illustrate her botanical books. Much like a photogram, Ana would lay her specimen on paper sensitized with photo chemicals, expose it to light and then rinse the paper with water. The areas covered by the plant remain white while the areas exposed to light turn a brilliant blue (cyan) revealing the form of the subject.

In Littoral Drift #848 (Pleasant Beach Watershed, Bainbridge Island, WA 12.05.17 Lapping Waves with Receding Tide and Splashes), pictured at the top, Riepenhoff uses the same process often with much larger pieces of paper. Instead of using a controlled water bath in a photo studio, she ‘rinses’ her cyanotypes with seawater. She stretches the paper on the shoreline and lets waves crash over it leaving their impression and initiating the chemical reaction that creates the image. The diverse elements of the seawater including sand, salt, algae, the byproducts of human existence on this planet, all affect the images in interesting and unexpected ways. The result is beautiful dynamic abstract images that evoke the form and movement of a wave on a two-dimensional surface.

Image at top: Meghann Riepenhoff, Littoral Drift #848 (Pleasant Beach Watershed, Bainbridge Island, WA 12.05.17 Lapping Waves with Receding Tide and Splashes), 2017. Cyanotypes. Courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York © Meghann Riepenhoff