Simphiwe Ndzube, Dondolo, the Witch Doctor's Assistant, 2020. Mixed media on canvas; 86 x 120 in. (218.4 x 304.8 cm). Funds, by exchange, from Mr. and Mrs. Fitzhugh Scott and Mrs. Hattie Louise Browning. © Simphiwe Ndzube. Image courtesy of the artist and Nicodim Gallery. Photo by Marten Elder.

Senga Nengudi, A.C.Q. I, 2016-2017. Dimensions variable. Installation dimensions at Sprüth Magers London: 78 3/4 × 178 × 126 inches. Collection of the Denver Art Museum, purchased with funds from the Contemporary Collectors’ Circle with additional support from Vicki and Kent Logan, Catherine Dews Edwards and Philip Edwards, Craig Ponzio, and Ellen and Morris Susman. © Senga Nengudi. Installation photography by Stephen White. Courtesy of Sprüth Magers, Thomas Erben Gallery, and Lévy Gorvy.

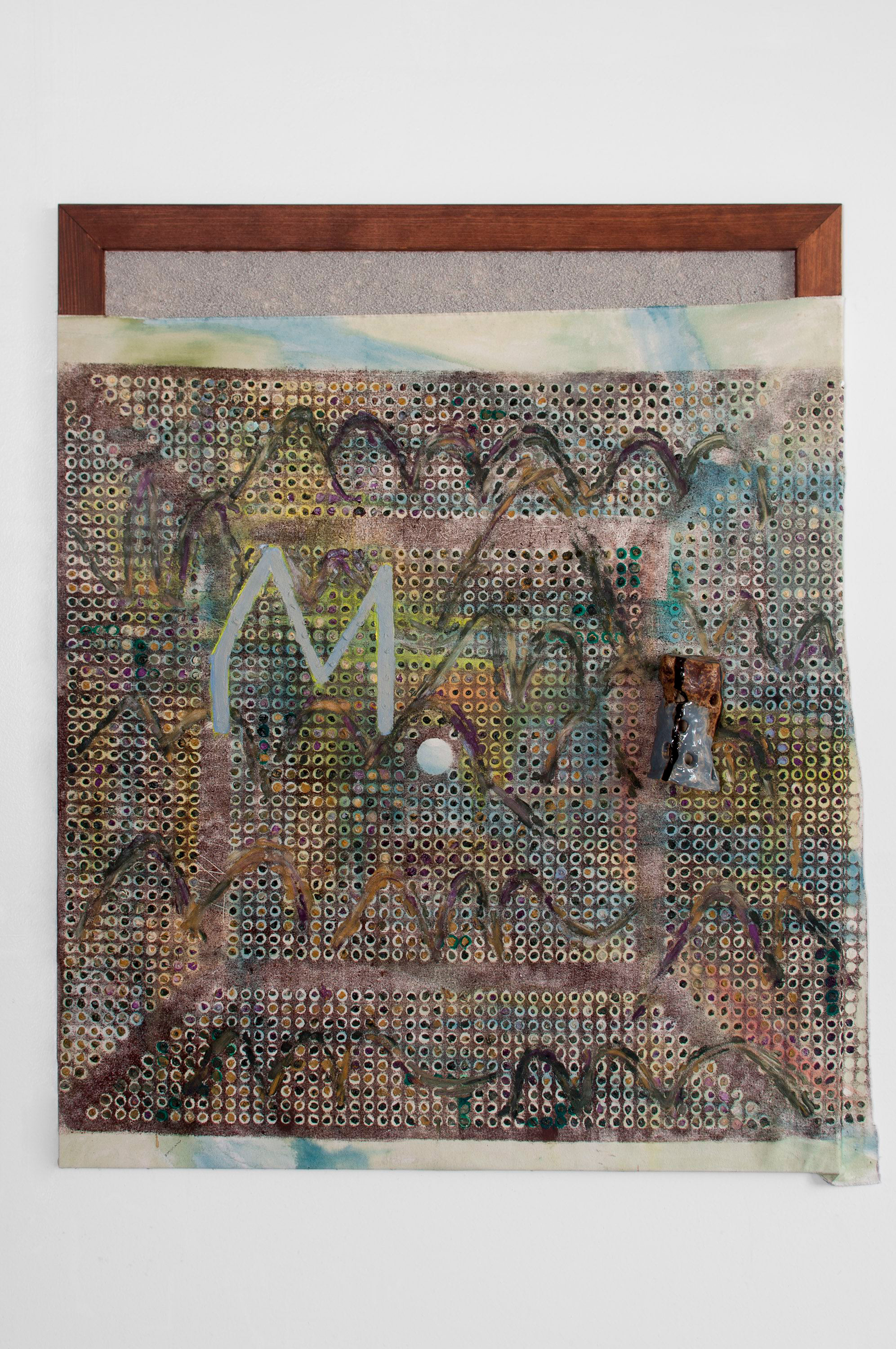

Jessica Jackson Hutchins, Letter M, 2015. Fabric, oil and acrylic paint, pumice, and glazed ceramic, 52 x 42 in. Anonymous gift, 2019.646. Image courtesy of the artist and Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York and Aspen. © Jessica Jackson Hutchins. Photo credit: Evan La Londe

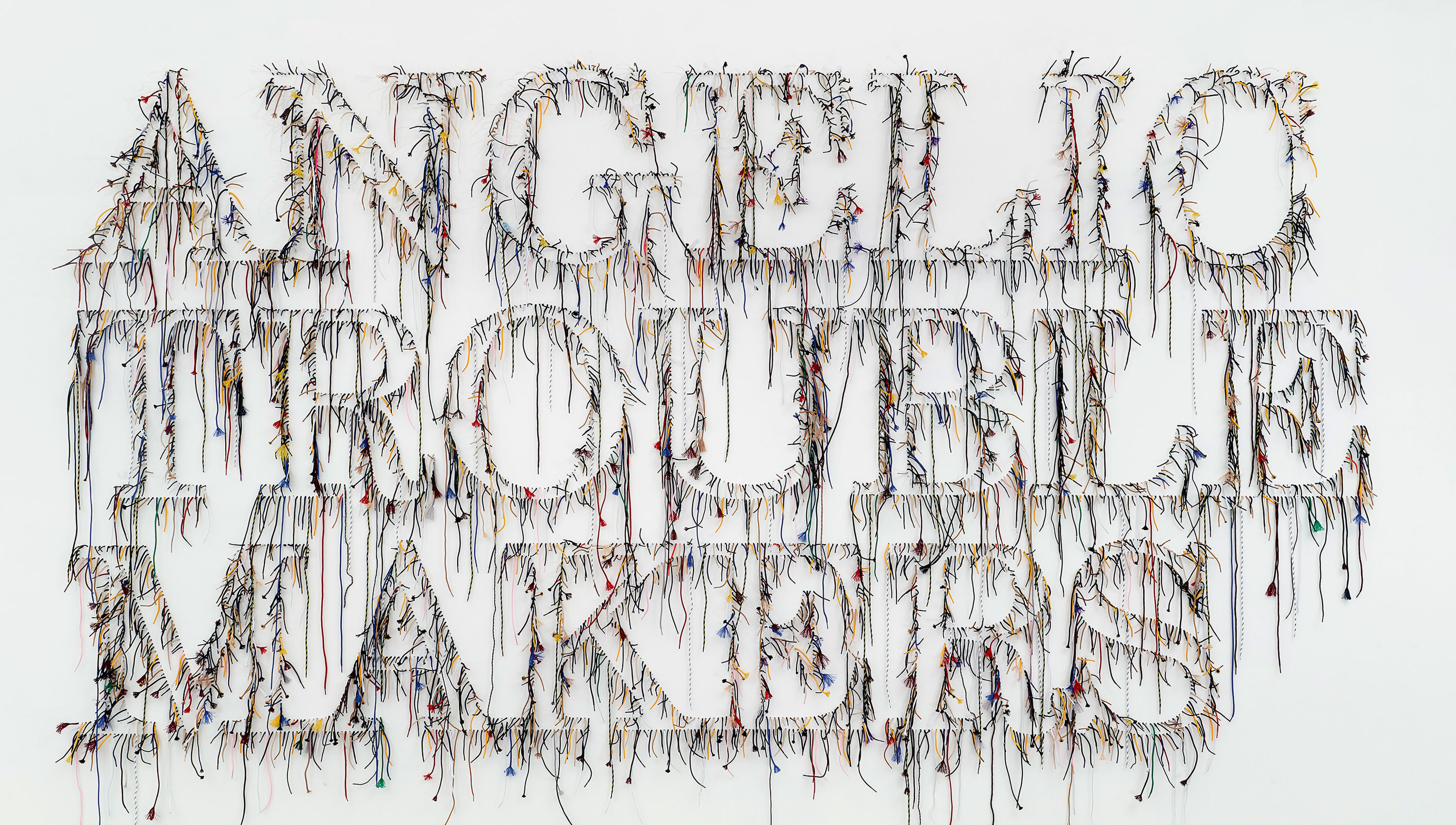

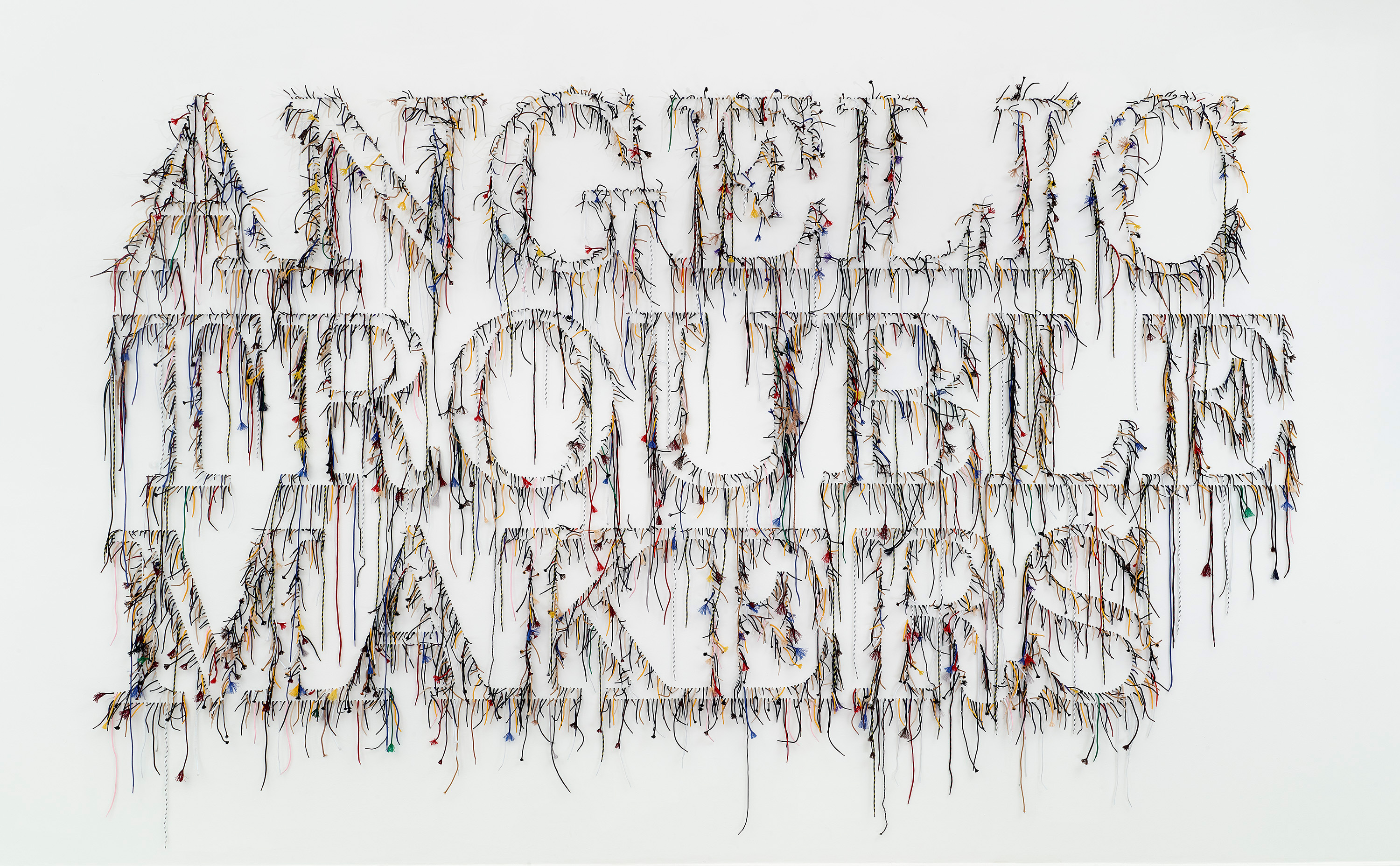

Nari Ward, Angelic Troublemakers, 2016. Shoelaces, 108 in. x 163 in. x 3.5 in. Funds from the Contemporary Collectors’ Circle with additional support from Vicki and Kent Logan, Catherine Dews Edwards and Philip Edwards, Craig Ponzio, Ellen and Morris Susman, and Bryon Adinoff and Trish Holland, 2021.38. © Nari Ward. Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, Seoul, and London. Photo by Max Yawney.

Simphiwe Ndzube

Since the beginning of his young career, Simphiwe Ndzube has been exploring the interplay between the real and the magical, stitching together personal accounts and historical memories to give life to his creations. Born in 1990 near Cape Town, South Africa, and living and working in Los Angeles, Ndzube constructs imaginary pocket universes as a way to frame larger conflicts about identity and histories, political power and struggles, and globalization and freedom. His outsized vivid canvases and dynamic sculptural installations oscillate between the beautiful and the grotesque, producing remarkable visual contrasts that captivate the viewers.

One of the most striking characteristics of Ndzube’s practice is his incorporation of second-hand clothing and accessories into the works, like seen in Dondolo, the Witch Doctor’s Assistant, 2020, (on view through October 10, 2021). According to the artist, he amasses textiles, wigs, and ribbons from the garment district and local thrift stores for his collection. Like the collage of his own eyes and hand into the painting, the garments bring a personal touch to Ndzube’s work, as they reference human bodies. He sources, gathers, and stitches these secondhand garments onto his canvases, stuffing the fabrics to make the amorphous bodies of his figures in works that become hybrids. For the artist, stitching fabric to his paintings and sculptures is a mode of mark-making, another way of projecting his own stories onto materials that contain cultural memories. The process is a meditative one; Ndzube questions whose bodies once wore these clothes, and what stories they tell.

The use of secondhand clothing and fabric that Ndzube uses are fundamental to understanding his work, as they are the elements by which viewers ground themselves in reality through their historical baggage. Due to their past functionality, these items convey the idea of an absent body or of a human memory, containing layers of history. They allow the viewers to relate their own bodies to the bodies of Ndzube’s figures by offering a sense of scale. In addition, with the presence of found objects, such as bicycle wheels, umbrellas, ropes, gloves, and hats, Nzdube’s fictitious universe becomes palpable, relatable, and familiar. He invites the audience to navigate the duality between the tangible and the imaginary, at times taking spectators out of their comfort zones into a fictional place where they can begin to explore issues of race, identity, and the making of history.

Nengudi juxtaposes hard, rigid, industrial materials with the soft elastic properties of stretched nylon.

Senga Nengudi

Using predominantly nylon mesh and found objects, much of Senga Nengudi’s sculptural works expand the limits of the body and its social norms. For Nengudi, the body not only becomes a site of physical creation, but a source of political resistance as she deals with themes such as racial identity, womanhood, ageing, endurance, body image, and social normativity. Nengudi’s installations are subtle and intimate, made out of materials that are discards and commonplace. Her work is interactive in nature, inviting viewers to be co-participants in her exploration of human relationships.

A.C.Q. I (2016–2017), which was on view in Topologies, takes a special position within Nengudi’s oeuvre. In this mixed-media installation, composed of refrigerator and air conditioner parts, fan, pantyhose, and sand, Nengudi juxtaposes hard, rigid, industrial materials with the soft elastic properties of stretched nylon. The work itself is performative, a foundational element in Nengudi’s practice, as the moving fan causes the soft elements to move. A.C.Q. I not only becomes activated as an object but also activates the space in which it is installed. In this particular piece, Nengudi moves from the elasticity of the body to the malleability of the mind, offering abstracted renderings of the human psyche as it navigates the obstacles of various stages of life, from parenthood, to career, relationships, and elder care. She threads nylon through pipe and stretches pantyhose to create forms that look like musical instruments with strings that tremble in the wake of a breeze from the nearby fan. The tension and the movement suggest that resilience and fragility can exist within the same moment.

Jessica Jackson Hutchins

Portland-based artist Jessica Jackson Hutchins incorporates everyday objects into her intricate assemblage pieces. Her paintings and sculptures tell personal stories in non-linear traditional ways, which she achieves by creating tangled surfaces that seem to organically intertwine. In the process of breaking free of form, Hutchins’ works become unrecognizable objects, inviting viewers to reimagine realities and project their own experiences onto the pieces themselves. By bringing the quotidian into her work, especially used or broken secondhand objects, she explores the relationship between humans and the material world.

For Letter M (2015), Hutchins combines media so that two-dimensional and sculptural surfaces join together creating an incredibly rich texture. The use of fabric (burlap sack), paint, pumice, and glazed ceramic, all call attention to the artist’s vast source of materials. The un-stretched canvas that envelops the frame horizontally acts like a screen that conceals the surface behind it, almost in a theatrical way. The recurrent pattern of colored painted dots on top of the canvas creates a feverish rhythm of personal marks, which is further emphasized by the repetition of the letter ‘M’ written all over the fabric. Even though the work might seem illegible, the audience is invited to look closer and examine its intimate surfaces. Hutchins’ inclusion of different scales—the macro and the micro—also encourage the viewer to become more engaged with the painting and its surroundings.

through material and text, Ward suggests the power of joining together for a cause.

Nari Ward

Another of the department’s recent acquisitions is Nari Ward’s Angelic Troublemakers of 2016, which is made entirely of colorful shoelaces. The work is emblematic of his larger practice in which he transforms found materials into works that bear significant political and social implications. For over 25 years, Ward has gathered and sculpted a range of materials including fire hoses, baseball bats, baby strollers, shopping carts, and other refuse.

By incorporating these elements into his sculptures, Ward transfers a level of meaning from the lives of the materials, and the people they may have served. Additionally, there is significant place-based meaning inherent to these mixed-media pieces, as Ward collected much of his materials throughout Harlem, where he lives and works. Shoelaces in particular also may be familiar to many different people across cultures. Tying shoelaces is typically the final step before an individual moves through space—as in to walk or march. Given that the phrase “Angelic Troublemakers” derives from a quote by civil rights activist and coordinator of the 1963 March on Washington, Bayard Rustin, there is a strong connection to the symbolic meaning of the material. Rustin proclaimed, “We need, in every community, a group of angelic troublemakers.” Therefore, through material and text, Ward suggests the power of joining together for a cause.